Fahrtwind - Aufzeichnungen einer Reisenden

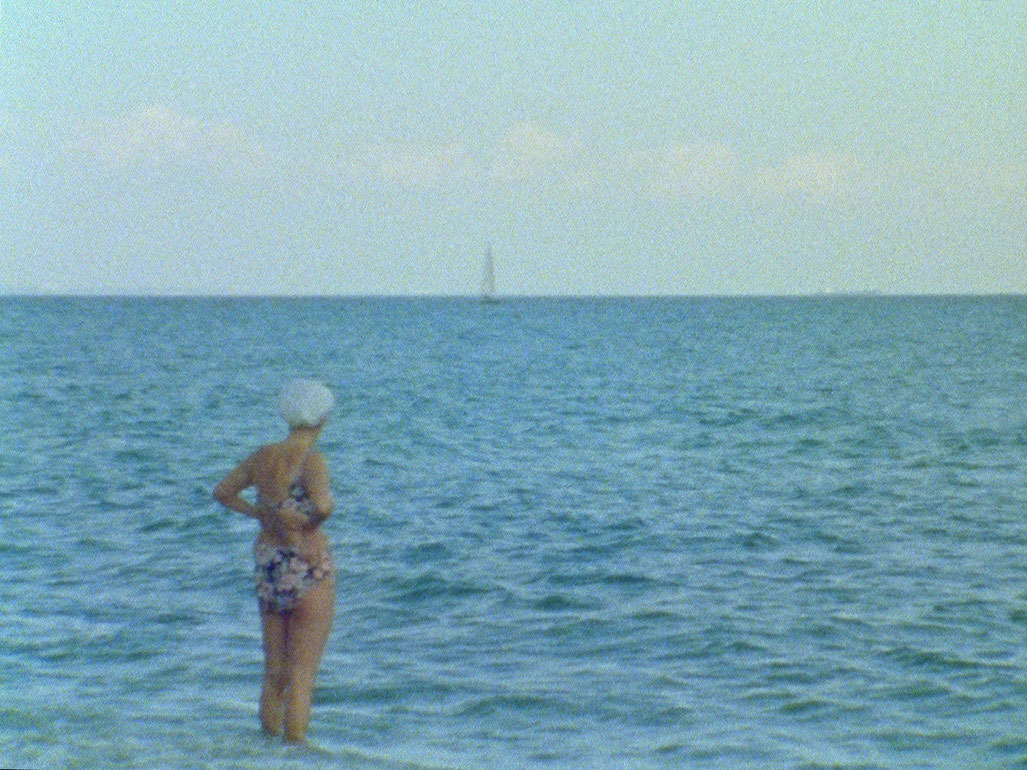

Die beiden Füße, die zu Beginn im Badewasser spielen, sind das Leitmotiv dieser Fahrt ins Blaue. Sie haben Lust auf Fahrtwind und Meer! Also macht die Reisende sich auf. Die Donau bringt sie auf einem Frachtschiff zunächst nach Bulgarien, dann fährt sie mit den verschiedensten Transportmitteln durch Rumänien, in die Ukraine, nach Georgien, Aserbaidschan und schließlich nach Kasachstan. Am Ende der Reise kommt sie mit einem eingegipsten Fuß aber ungebrochen nach Wien zurück als ob die Füße erst ruhig gestellt werden müssten, bevor die Reise enden kann.

Ein Reisefilm, bei dem die Augen (die Kamera) nicht genug bekommen vom Unterwegssein, von in ihrer Mannigfaltigkeit flirrenden Impressionen, von fast ehrfurchtsvollen Eindrücken atemberaubender Landschaften, von dem Hin und Her des Straßenlebens und vor allem von der Vielfalt der Bewegungen, der Emotionen und des Minenspiels in den Gesichtern der Menschen.

Die Tonebene unternimmt mit einer subtilen Montage aus Raumton, Stimmen und a capella gesungenen Liedern ihre eigenen Reise - nie lippensynchron. Ein Stummfilm zum Hören, ein Film mit Bildern und Tönen, die unabhängig von einander zu operieren scheinen. Der Film wirkt gerade durch das, was er Genre untypisch nicht liefert, federleicht lebendig und Luft und Atmosphäre durchatmet. Er funktioniert ohne Interviews, ohne historische oder zeitaktuelle Informationen, ohne Zahlen oder gesellschaftskritische Bemerkungen.

Der Weg führt über Berge und Meere, durch Großstädte und Wüstenlandschaften, in ein Kloster, eine Romasiedlung, vorbei an Tanzenden in Odessa und schnarchenden Männern in einer Kajüte, der alltäglichen Schwerarbeit in einem kaukasischen Bergdorf, in die Welt der Reichen und die Häuser der Armen, um in einer kasachischen Wohnung zur erzwungenen Ruhe zu kommen. Ein buntes Mosaik aus Lebensfreude, Neugier und dem Vertrauen darauf, dass alles was kommt, willkommen ist.

(Birgit Flos)

Das Ziel von Fahrtwind ist es, sich auf den „ersten Blick“ in die Welt zu verlieben.

Es ist überflüssig zu sagen, dass jeder Moment nur einen Moment lang existiert. Aber das ist es, was mir auf meiner Reise jedes Mal bewusst geworden ist, wenn ich Bilder oder Töne aufgenommen habe. Man kann nicht schnell oder lange genug schauen, um nicht die meisten dieser Momente zu versäumen. Das sind keine besonderen Momente, doch sie sind schön in ihrer Einzigartigkeit. Es ist, als würde man mit einem Schmetterlingsnetz herumlaufen. 24 Impulse von alltäglichem Licht, die sich pro Sekunde in das Gedächtnis des Filmmaterials einbrennen.

Bilder, Töne, Assoziationen, Atmosphären, Sinnlichkeit und Rhythmus tanzen miteinander und erzählen Geschichten. Meine Entscheidung beinahe keinen Text zu verwenden, lädt die ZuschauerInnen dazu ein ihre eigenen Reisen und Erfahrungen zu machen.

(Bernadette Weigel)

Trailer online

slow criticism | Fair Wind (Fahrtwind) by Chris Fujiwara (Kritik)

In the absence of any knowledge about the journey documented by the film, apart from the place names that appear superimposed in white type as each new location is reached, we must be satisfied with other certainties while watching Bernadette Weigel´s Fair Wind – Notes of a Traveler (Fahrtwind – Aufzeichnungen einer Reisenden). Above all, with the confidence of feeling that Weigel communicates: a confidence that comes from love, and Fair Wind is nothing if not a film in love with light. With each shot, we seem to see as much light as can be packed into a Super-8 frame. Rather than a painful brightness, the effect is that of contented saturation, visual plenitude.

If the image is constantly in a condition of being just right, the titles give both too much and too little: too much information, since the names of towns are likely to be unfamiliar and anyway of no use, and too little, since the important things – the links between these places, the motives that drive the filmmaker from one to the next – are always elided. Denied the code that would govern Weigel´s choices, the viewer more readily grasps the arbitrariness of any code and any choice. Which is to say that instead of committing herself to the rules of a discursive genre Weigel locates her film in the negative spaces lying around the genres she brushes past: travel journal or self-portrait, post card or essay.

The space of the film is not just "post-Communist Eastern Europe and Central Asia", but also the space of a hundred or a thousand separate encounters between the filmmaker (once she has set off from her home in Vienna) and the people of the post-Communist world. There is no program, simply the succession of frames, highlighting the texture and the squareness of the image, making possible a kind of explosion of reality in movement, color, industrial forms (the Odessa funicular with its solid-color cars) and forms of ritual (elderly Ukrainians dancing to a town-square band´s performance of "In the Mood"). Every view, however enchanted, still implies what is, and remains, a social and historical context, but that context becomes displaced – not so much "made strange" as offered up to the delirious purposelessness of cinema, of this cinema.

Fair Wind is a film without alienation, so blissfully so that it is not even made against alienation. Fair Wind may perhaps be criticized for fetishizing the obsolete, for seizing hungrily on what it loves too sentimentally. But the success of the film has to do with neither alienation nor its opposite but with the filmmaker´s constant ability to find mystery, as if receiving it as a gift: a young couple in a partly darkened apartment, a card game on the grass in the country, shadows of leaves fading in and out dramatically on a white plaster wall, the broad smile of an elderly woman refugee, the pleasure of two nuns as they pull on bell ropes until they are lifted up in the air. Everything has just the expressiveness that it has: no excess or imbalance is caused by an expressive intention in the world in front of the camera, or on the other side by any need on the part of the camera to justify its being where it is.

The sounds that overlay the images draw very selectively from the field of sounds that must have been available, so that the movement of people with its urgency or randomness is never allowed to determine the pace and balance of the image. A gentle and graceful musique concrète of boat and train engines lulls the eye across sequences of short discrete shots; a lone cat´s meowing evokes a vacancy of night in an urban residential neighborhood. The brilliance of the soundtrack is a vital resource in the game Weigel´s film plays: a game between openness and closure, between the "open" of a voyage without a destination and the "closed" of a frame that is never going to run out of ways to fill itself.

Chris Fujiwara was the Artistic Director of Edinburgh International Film Festival in 2013/2014 and is the author of books on Jerry Lewis, Otto Preminger, and Jacques Tourneur.

Fahrtwind - Aufzeichnungen einer Reisenden

2013

Österreich

82 min