Pensao Globo

A man faces his approaching death. He takes a journey, his last perhaps, and ends up at the Pensão Globo in Lisbon, where he sets out on aimless excursions through the city. The film depicts a life in a state of transition. Sometimes it´s like I´m already gone, become a ghost of myself.

(Matthias Müller)

The wonder of Matthias Müller´s experimental film work comes from letting you into this most private of all private worlds, the diary where memory and desire are layered one on top of the other. Non-linear but intensely dramatic, visually complicated but emotionally direct, this remarkable cycle of work opens itself up to you like a secret diary being read for the very first time.

(Peter Goddard)

More Texts

A Journey into the Light: Matthias Müller´s Film Pensão Globo (Article)

Daniel Kothenschulte, In: Senses of Cinema, Feb. 2006

Translation: Nick Grindells

“Film is Forever” was a slogan once used by an already ailing Hollywood industry to insist on the everlasting value of its icons. Sooner or later, however, anyone who decides to entrust their art to a chemical product as sensitive as film emulsion will notice that this is not the case. Film fades, changes, disappears. And even if one leading manufacturer now gives a 100-year warranty on its material, this doesn´t alter the fact that films, unlike marble sculptures, but not unlike ourselves, are only granted a limited time on this planet.

Matthias Müller´s films are always about both the eternal and the volatile qualities of cinema. They exaggerate the unreality and clinical perfection of the Hollywood studio films of the 1950s, quoting its sets and colours (Home Stories, 1990; Pensão Globo, 1997) or even reconstructing them in minute detail (Alpsee, 1994). But, at the same time, these attributes, known in film jargon as the production values, are exposed to decay – a decay which on closer inspection proves to include wilful acts of creation. As his own lab technician, Müller is responsible not only for subsequent wear and tear, but also for the initial developing of his own film material.

As a result, in all of Müller´s works the living quality of film images is experienced through their passing away. This is achieved on the one hand by inflicting external damage on the film material, with scratches and stains making it look like the decomposed nitrate of old silent movies. Another technique results from the optical copying process, with a pulsating flicker superimposed over the picture, making images run into each other and giving the halogen projection light the grace of candlelight, a motif traditionally associated with both life and death.

In painting, the limited life of candles has been the stuff of allegory for centuries. In film history, one need only think of the famous sea of candles scene in Fritz Lang´s Der Mude Tod (Destiny, 1921), later cited by Luis Buñuel as the image that made him sense his calling as a filmmaker. In his first long film, Aus der Ferne – The Memo Book (1989), which is also his first work dealing with the theme of AIDS, Müller further heightens the impression of candlelight´s warmth and transience by using a sepia tone throughout. This kind of coloration, applied to the film material after developing, was routinely used during the silent film era.

In many of his works, Müller quotes the aura of preciousness, fragility and pathos that surrounds the surviving artefacts of early movie history. The blue-tinted seascape, Sleepy Haven (1993), and the 2-minute Sternenschauer – Scattering Stars (1994) based on it, makes use of this effect. In this, Müller follows in the footsteps of the American avant-garde filmmaker and artist Joseph Cornell, who saved found fragments of film and then re-edited them, making no distinction between Hollywood and amateur film products when it came to detecting the immanent magic of the material.

Aus der Ferne – The Memo Book

With this continual impression of volatility and fragility, it is not hard to identify death as a subject in Müller´s œuvre. In some cases it only comes through over the course of the film, as in Pensão Globo (1997), where it is unmistakably heard in the form of a voice-over with recordings of an AIDS-patient. In this film, Müller returns to the location of Lisbon and to the subject matter of Aus der Ferne – The Memo Book. This first autobiographical meditation on the death of a friend from AIDS combined personal and found fragments, forming a melancholic love story where the glamour of a candelabra illuminating the dead friend merge with excerpts from Hollywood musicals or Siegfried´s bath in dragon blood from Lang´s Die Nibelungen (1924). Operation scenes from a medical teaching film burst into the dreamy, stylised world of Aus der Ferne (the motif of a beating heart laid bare returns in Alpsee), while also repeating this fragile work´s pulsating overall rhythm.

The main difference between Pensão Globo and its predecessor is the use of colour film throughout. Whereas Müller´s early works sought to resemble silent movies, here a different bygone film æsthetic is emulated: the coloration of early, long-obsolete colour processes. But instead of the radiant Technicolor used by Douglas Sirk, the melodramatist he much admires, Müller has used his own laboratory to create a deceptively convincing imitation of the reduced and intensified colours of 1940s Kodachrome stock, the preferred expressive medium of the American avant-garde. This effect is achieved by strongly accentuating red and green. As a result, Pensão Globo seems at first glance like a lost fragment of Hans Richter´s episodic Surrealist film, Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947). Its narrative structure, too – a closed, circular journey – is reminiscent of the kind of oneiric tale of search and loss told in Max Ernst´s contribution to Richter´s film.

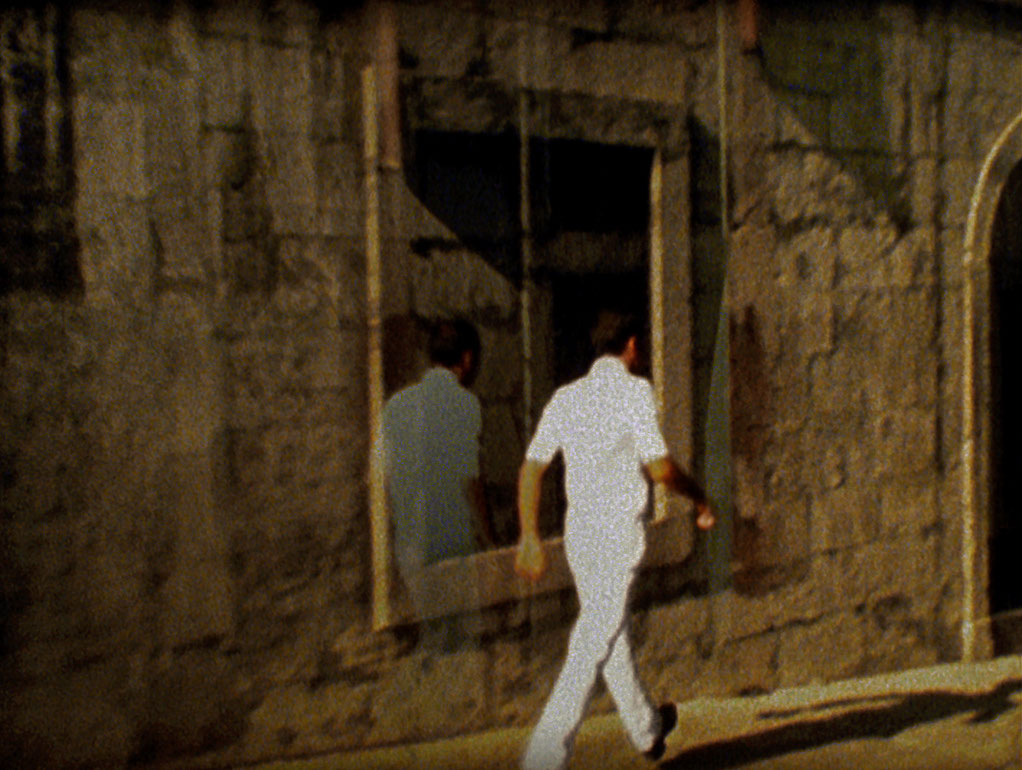

The story is framed by the preparation of a hotel room by a maid. The opening scene, placed before the credits, shows her putting a sheet on a red mattress, introducing the simulated double exposure used throughout the film as a stylistic principle. Using double projection onto a sheet of opaque glass, Müller combines shots of identical scenes from slightly different angles. This creates the effect of a ghost shot, another technique frequently used when dealing with the paranormal, both in classical avant-garde cinema and in Hollywood. Late in the film, the voice-over refers directly to this ghost motif: “Sometimes it´s like I´m already gone, become a ghost of myself”.

Pensão Globo

The film´s narrator is introduced as the silhouette of a man shown straining to climb staircases that fade into one another. He signs his name in the hotel ledger of Pensão Globo, unpacks his suitcase and prepares for his imminent death (the commentary assembled by Müller from recordings of an HIV patient leaves us in no doubt about this). He is accompanied by the ghosts of his past, who may have fallen victim to the illness themselves: “I bring them all with me, the ones who came before”. Memories of the dead are constant companions, corresponding (like the mirror into which the dying man no longer dares to look) with the photographic doubling of the copying process.

The impression of a closed, circular plot, enveloping the viewer, is strengthened by the soundtrack, created, as in most of Müller´s films, by Dirk Schaefer, in this case a montage that extends the found footage montage to the acoustic level. A loop made from an old fado exerts a powerful pull on the listener. Hallucinatory visual effects like the flickering merging of objects in the hotel room are given an audio dimension with rattling or tropically sultry crackling and rustling sounds. While the voice-over tells the sick man´s medical case history, the soundtrack adds another layer of reflection, as the voice is distorted in the style of a 1950s B-movie, giving the feel of a science-fiction story. This is reinforced by one of the few pieces of visual found footage in the film, an excerpt from Jack Arnold´s classic movie, The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957).

In this film, a man sees himself as the carrier of an incurable disease when he discovers that he is gradually but inexorably getting smaller and smaller. In Arnold´s film, the voice-over technique borrowed from film noir was a simple way of introducing a metaphysical level, as Mister C´s constant shrinking causes him to recognize a previously invisible side of divine creation.

Another found footage element is a super-8 sequence showing a mother with her baby (pictures shot by the director´s father). In a series of delirious cuts, Müller confronts his central figure with the redness of blood and wine. A shave becomes an unstoppable bloodletting scene, like in Martin Scorsese´s short film, The Big Shave (1967). In pictures reminiscent of home movies, the central character is seen visiting Lisbon´s tourist attractions and a botanical garden. The vulnerable but resilient leaves of cactuses, into which travellers have scratched their initials, give way to close-up shots of the diseased skin of the central figure. While red blossoms close, the man seeks refuge in a tightly buttoned red shirt which he handles like a precious curtain. But then the maid is already back, tearing the sheet from the red mattress in preparation for its next occupant.

Like most of Matthias Müller´s films, Pensão Globo leads us into a domain between private and public iconography. It has often been pointed out that mass culture is capable of penetrating deeply into the private æsthetic of our lives through individual appropriation. In memory, a song or film will have connotations as strong as any photo we took ourselves. In our living environment, our own artefacts and those created by others merge to form an identity-giving whole. While European art didn´t discover amateur photography until around 1970 (in artists like Hans-Peter Feldmann or Gerhard Richter), American avant-garde cinema adopted the role of mediator between private and public iconography early on. The 1920s saw the founding of societies for fans of art films in the United States, recently rediscovered by researchers. In the 1930s, Joseph Cornell´s montages of home movies and Hollywood fragments openly breached the divide between professional and private æsthetics in film.

Although Matthias Müller is now rightly counted among the pioneers of the found footage movement in experimental film, with his use of private and amateur film making him eminently suited for inclusion in a show entitled “Private Affairs”, one should not forget the important role played by private material in the past history of the avant-garde cinema that provided inspiration for Müller´s work.

In her writings, Maya Deren, a pioneer of American art movies, argued strongly against dismissing amateur products in comparison to professional work:

Like the amateur still-photographer, the amateur filmmaker can devote himself to capturing the poetry and beauty of places and events and, since he is using a motion picture camera, he can explore the vast world of the beauty of movement. (1)

Although private footage makes up only a small part of Pensão Globo, long passages quote the look of old home movies and classic works of American avant-garde cinema. In this way, the personal is counterbalanced with something timeless and impersonal, corresponding to the intended content of the film, which aims to take reported experiences collected by Müller among his own friends and from published accounts like the AIDS diaries of Hervé Guibert, Derek Jarman and Wolfgang Max Faust, and raise them to a general level which can at the same time be read as “private”. The most important contribution came from Mike Hoolboom, who supplied journal-like texts about his illness and himself voiced all the passages selected by Müller. In this way, appropriation led to a reprivatization of the material.

In the structure of the film, this results in a narration compatible with the forms of the classical narrative cinema of the 1940s, the idea of a super-real melodrama to which an avant-gardist like Cornell also felt drawn. In his masterful merging of private and public fragments, Müller creates an approach to the subject of dying from AIDS that can be accessed at both individual and general levels. By the time he made this film, he had long since discovered a convincing model for the fragility of life itself in his pulsating, flickering treatment of film material in a constant process of creation and decay.

Translation: Nick Grindells

“Film is Forever” was a slogan once used by an already ailing Hollywood industry to insist on the everlasting value of its icons. Sooner or later, however, anyone who decides to entrust their art to a chemical product as sensitive as film emulsion will notice that this is not the case. Film fades, changes, disappears. And even if one leading manufacturer now gives a 100-year warranty on its material, this doesn´t alter the fact that films, unlike marble sculptures, but not unlike ourselves, are only granted a limited time on this planet.

Matthias Müller´s films are always about both the eternal and the volatile qualities of cinema. They exaggerate the unreality and clinical perfection of the Hollywood studio films of the 1950s, quoting its sets and colours (Home Stories, 1990; Pensão Globo, 1997) or even reconstructing them in minute detail (Alpsee, 1994). But, at the same time, these attributes, known in film jargon as the production values, are exposed to decay – a decay which on closer inspection proves to include wilful acts of creation. As his own lab technician, Müller is responsible not only for subsequent wear and tear, but also for the initial developing of his own film material.

As a result, in all of Müller´s works the living quality of film images is experienced through their passing away. This is achieved on the one hand by inflicting external damage on the film material, with scratches and stains making it look like the decomposed nitrate of old silent movies. Another technique results from the optical copying process, with a pulsating flicker superimposed over the picture, making images run into each other and giving the halogen projection light the grace of candlelight, a motif traditionally associated with both life and death.

In painting, the limited life of candles has been the stuff of allegory for centuries. In film history, one need only think of the famous sea of candles scene in Fritz Lang´s Der Mude Tod (Destiny, 1921), later cited by Luis Buñuel as the image that made him sense his calling as a filmmaker. In his first long film, Aus der Ferne – The Memo Book (1989), which is also his first work dealing with the theme of AIDS, Müller further heightens the impression of candlelight´s warmth and transience by using a sepia tone throughout. This kind of coloration, applied to the film material after developing, was routinely used during the silent film era.

In many of his works, Müller quotes the aura of preciousness, fragility and pathos that surrounds the surviving artefacts of early movie history. The blue-tinted seascape, Sleepy Haven (1993), and the 2-minute Sternenschauer – Scattering Stars (1994) based on it, makes use of this effect. In this, Müller follows in the footsteps of the American avant-garde filmmaker and artist Joseph Cornell, who saved found fragments of film and then re-edited them, making no distinction between Hollywood and amateur film products when it came to detecting the immanent magic of the material.

Aus der Ferne – The Memo Book

With this continual impression of volatility and fragility, it is not hard to identify death as a subject in Müller´s œuvre. In some cases it only comes through over the course of the film, as in Pensão Globo (1997), where it is unmistakably heard in the form of a voice-over with recordings of an AIDS-patient. In this film, Müller returns to the location of Lisbon and to the subject matter of Aus der Ferne – The Memo Book. This first autobiographical meditation on the death of a friend from AIDS combined personal and found fragments, forming a melancholic love story where the glamour of a candelabra illuminating the dead friend merge with excerpts from Hollywood musicals or Siegfried´s bath in dragon blood from Lang´s Die Nibelungen (1924). Operation scenes from a medical teaching film burst into the dreamy, stylised world of Aus der Ferne (the motif of a beating heart laid bare returns in Alpsee), while also repeating this fragile work´s pulsating overall rhythm.

The main difference between Pensão Globo and its predecessor is the use of colour film throughout. Whereas Müller´s early works sought to resemble silent movies, here a different bygone film æsthetic is emulated: the coloration of early, long-obsolete colour processes. But instead of the radiant Technicolor used by Douglas Sirk, the melodramatist he much admires, Müller has used his own laboratory to create a deceptively convincing imitation of the reduced and intensified colours of 1940s Kodachrome stock, the preferred expressive medium of the American avant-garde. This effect is achieved by strongly accentuating red and green. As a result, Pensão Globo seems at first glance like a lost fragment of Hans Richter´s episodic Surrealist film, Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947). Its narrative structure, too – a closed, circular journey – is reminiscent of the kind of oneiric tale of search and loss told in Max Ernst´s contribution to Richter´s film.

The story is framed by the preparation of a hotel room by a maid. The opening scene, placed before the credits, shows her putting a sheet on a red mattress, introducing the simulated double exposure used throughout the film as a stylistic principle. Using double projection onto a sheet of opaque glass, Müller combines shots of identical scenes from slightly different angles. This creates the effect of a ghost shot, another technique frequently used when dealing with the paranormal, both in classical avant-garde cinema and in Hollywood. Late in the film, the voice-over refers directly to this ghost motif: “Sometimes it´s like I´m already gone, become a ghost of myself”.

Pensão Globo

The film´s narrator is introduced as the silhouette of a man shown straining to climb staircases that fade into one another. He signs his name in the hotel ledger of Pensão Globo, unpacks his suitcase and prepares for his imminent death (the commentary assembled by Müller from recordings of an HIV patient leaves us in no doubt about this). He is accompanied by the ghosts of his past, who may have fallen victim to the illness themselves: “I bring them all with me, the ones who came before”. Memories of the dead are constant companions, corresponding (like the mirror into which the dying man no longer dares to look) with the photographic doubling of the copying process.

The impression of a closed, circular plot, enveloping the viewer, is strengthened by the soundtrack, created, as in most of Müller´s films, by Dirk Schaefer, in this case a montage that extends the found footage montage to the acoustic level. A loop made from an old fado exerts a powerful pull on the listener. Hallucinatory visual effects like the flickering merging of objects in the hotel room are given an audio dimension with rattling or tropically sultry crackling and rustling sounds. While the voice-over tells the sick man´s medical case history, the soundtrack adds another layer of reflection, as the voice is distorted in the style of a 1950s B-movie, giving the feel of a science-fiction story. This is reinforced by one of the few pieces of visual found footage in the film, an excerpt from Jack Arnold´s classic movie, The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957).

In this film, a man sees himself as the carrier of an incurable disease when he discovers that he is gradually but inexorably getting smaller and smaller. In Arnold´s film, the voice-over technique borrowed from film noir was a simple way of introducing a metaphysical level, as Mister C´s constant shrinking causes him to recognize a previously invisible side of divine creation.

Another found footage element is a super-8 sequence showing a mother with her baby (pictures shot by the director´s father). In a series of delirious cuts, Müller confronts his central figure with the redness of blood and wine. A shave becomes an unstoppable bloodletting scene, like in Martin Scorsese´s short film, The Big Shave (1967). In pictures reminiscent of home movies, the central character is seen visiting Lisbon´s tourist attractions and a botanical garden. The vulnerable but resilient leaves of cactuses, into which travellers have scratched their initials, give way to close-up shots of the diseased skin of the central figure. While red blossoms close, the man seeks refuge in a tightly buttoned red shirt which he handles like a precious curtain. But then the maid is already back, tearing the sheet from the red mattress in preparation for its next occupant.

Like most of Matthias Müller´s films, Pensão Globo leads us into a domain between private and public iconography. It has often been pointed out that mass culture is capable of penetrating deeply into the private æsthetic of our lives through individual appropriation. In memory, a song or film will have connotations as strong as any photo we took ourselves. In our living environment, our own artefacts and those created by others merge to form an identity-giving whole. While European art didn´t discover amateur photography until around 1970 (in artists like Hans-Peter Feldmann or Gerhard Richter), American avant-garde cinema adopted the role of mediator between private and public iconography early on. The 1920s saw the founding of societies for fans of art films in the United States, recently rediscovered by researchers. In the 1930s, Joseph Cornell´s montages of home movies and Hollywood fragments openly breached the divide between professional and private æsthetics in film.

Although Matthias Müller is now rightly counted among the pioneers of the found footage movement in experimental film, with his use of private and amateur film making him eminently suited for inclusion in a show entitled “Private Affairs”, one should not forget the important role played by private material in the past history of the avant-garde cinema that provided inspiration for Müller´s work.

In her writings, Maya Deren, a pioneer of American art movies, argued strongly against dismissing amateur products in comparison to professional work:

Like the amateur still-photographer, the amateur filmmaker can devote himself to capturing the poetry and beauty of places and events and, since he is using a motion picture camera, he can explore the vast world of the beauty of movement. (1)

Although private footage makes up only a small part of Pensão Globo, long passages quote the look of old home movies and classic works of American avant-garde cinema. In this way, the personal is counterbalanced with something timeless and impersonal, corresponding to the intended content of the film, which aims to take reported experiences collected by Müller among his own friends and from published accounts like the AIDS diaries of Hervé Guibert, Derek Jarman and Wolfgang Max Faust, and raise them to a general level which can at the same time be read as “private”. The most important contribution came from Mike Hoolboom, who supplied journal-like texts about his illness and himself voiced all the passages selected by Müller. In this way, appropriation led to a reprivatization of the material.

In the structure of the film, this results in a narration compatible with the forms of the classical narrative cinema of the 1940s, the idea of a super-real melodrama to which an avant-gardist like Cornell also felt drawn. In his masterful merging of private and public fragments, Müller creates an approach to the subject of dying from AIDS that can be accessed at both individual and general levels. By the time he made this film, he had long since discovered a convincing model for the fragility of life itself in his pulsating, flickering treatment of film material in a constant process of creation and decay.

Orig. Title

Pensao Globo

Pensao Globo

Year

1997

1997

Country

Germany

Germany

Duration

15 min

15 min