Coming Attractions

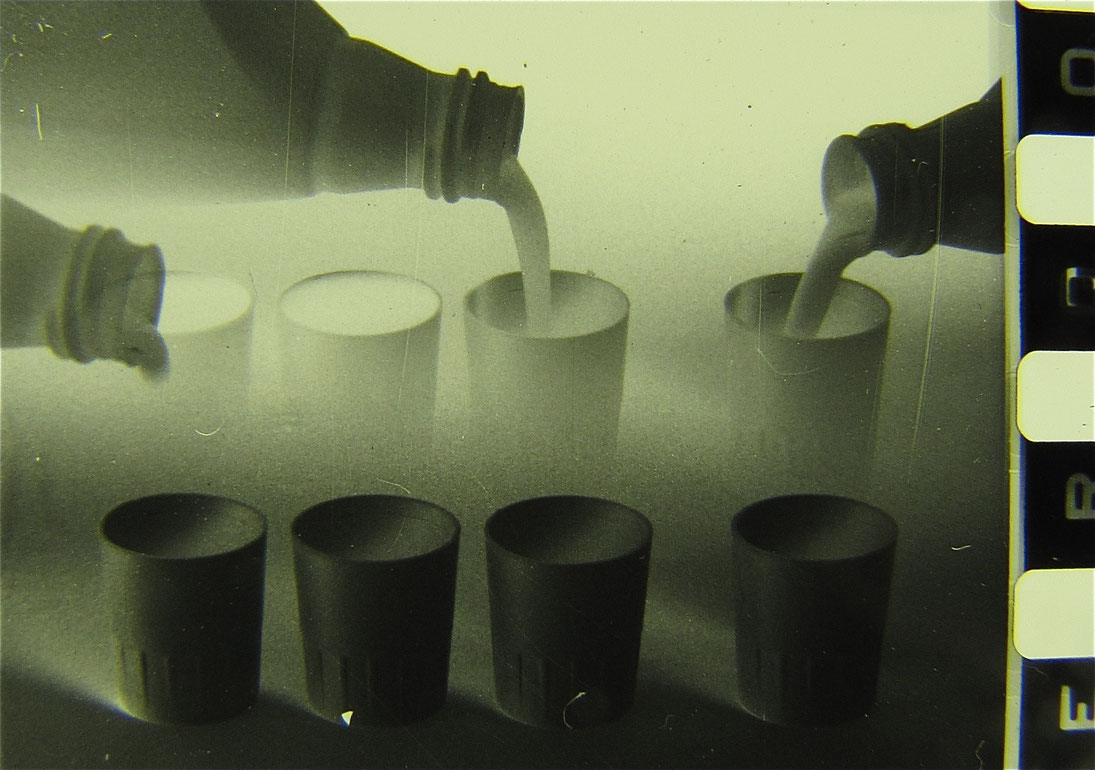

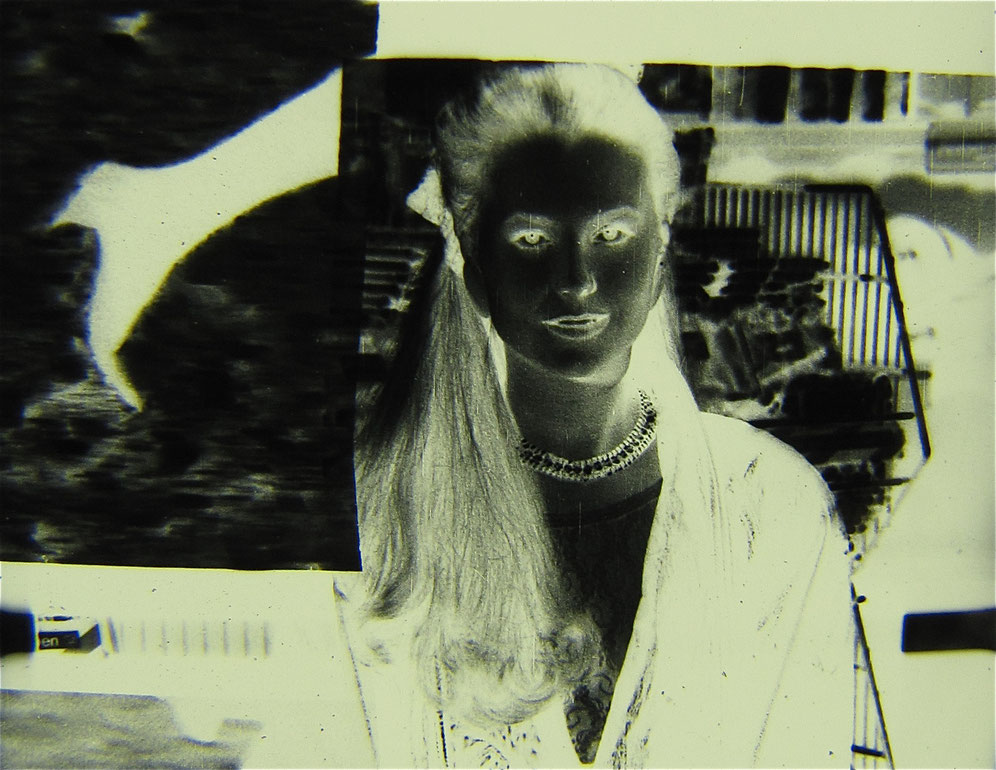

A negative image of a man's eyes in a car's rearview mirror. The countershot shows a smiling woman, and her wholly unambiguous facial expressions call our attention to the image's left-hand side, where film clips take shape in a flickering split screen. They show models, cups and various types of vehicles, which are then worked over thoroughly in the next 25 minutes: Coming Attractions. The title refers to both the nature of advertising films and early cinema, the 'cinema of attractions.' The initial visual contact juxtaposes the two genres through editing, and together with avant-garde film they represent the basic troika for 11 chapters in which Peter Tscherkassky examines the varying relationships between these three worlds of moving images. His film, a look at cinematic history through the rearview mirror, has been enriched with references in the carefully worded headings, to painting, music and film theory, in the form of wordplay. At the same time, what is being shown is fairly obvious.

Using screen tests for commercials that were not meant to be preserved, Tscherkassky, the master of found footage, composed Coming Attractions in minute darkroom work. He adopted a variety of approaches in the individual chapters and, understandably, reveled in the absurd character of his raw material. Associations and cross connections are created, some of them mischievous and others with a deeper meaning: from the 'Ballet monotonique' of the daily grind at work, inspired by Léger, and actresses in advertising films who are doomed to mechanically repeat the same actions again and again, to the downright surreal scene of a model with an inflatable hood drier and a saxophone, not to forget a farewell scene in which two seemingly bewildered Pasolini actors encounter a sheepishly grinning tractor driver from a dumpling-mix commercial. This amusing cinematic cross-section presented as a cryptic visual poem, or poem of visuals, showing (un)conscious missteps is amusing, lighthearted and playful.

(Christoph Huber)

Coming Attractions and the construction of its images are woven around the idea that there is a deep, underlying relationship between early cinema and avant-garde film. Tom Gunning was among the first to describe and investigate this notion in a systematic and methodical manner in his well known and often quoted essay: 'An Unseen Energy Swallows Space: The Space in Early Film and Its Relation to American Avant-Garde Film' (in: John L. Fell [ed.], Film Before Griffith, Berkeley 1983).

Coming Attractions additionally addresses Gunning's concept of a 'Cinema of Attractions'. This term is used to describe a completely different relation between actor, camera and audience to be found in early cinema in general, as compared to the 'modern cinema' which developed after 1910, gradually leading to the narrative technique of D.W.Griffith. The notion of a 'Cinema of Attractions' touches upon the exhibitionistic character of early film, the undaunted show and tell of its creative possibilities, and its direct addressing of the audience.

At some point it occured to me that another residue of the cinema of attractions lies within the genre of advertising: Here we also often encounter a uniquely direct relation between actor, camera and audience.

The impetus for Coming Attractions was to bring the three together: commercials, early cinema, and avant-garde film.

(P. Tscherkassky)

COMING ATTRACTIONS / director's notes

COMING ATTRACTIONS

(2010, 35mm, b/w, 25 min 10 sec; soundtrack: Dirk Schaefer)

Notes by the director

Coming Attractions and the construction of its images are woven around the idea that there is a deep, underlying relationship between early cinema and avant-garde film. Tom Gunning was among the first to describe and investigate this notion in a systematic and methodical manner in his well known and often quoted essay: `An Unseen Energy Swallows Space: The Space in Early Film and Its Relation to American Avant-Garde Film (in: John L. Fell [ed.], Film Before Griffith, Berkeley 1983).

Coming Attractions additionally addresses Gunning's concept of a `Cinema of Attractions. This term is used to describe a completely different relation between actor, camera and audience to be found in early cinema in general, as compared to the `modern cinema which developed after 1910, gradually leading to the narrative technique of D.W.Griffith. The notion of a `Cinema of Attractions touches upon the exhibitionistic character of early film, the undaunted show and tell of its creative possibilities, and its direct addressing of the audience.

At some point it occured to me that another residue of the cinema of attractions lies within the genre of advertising: Here we also often encounter a uniquely direct relation between actor, camera and audience.

The impetus for Coming Attractions was to bring the three together: commercials, early cinema, and avant-garde film.

Coming Attractions is divided into eleven individually titled chapters:

Chapter #1, `Cinema of Attraction, attempts a literal re-interpretation of a cinema of attractions.

---------

Cubist Cinema _1: An Unseen Energy Swallows Face refers to Tom Gunnings above mentioned essay.

---------

The title of chapter #3, `Le Sang d'un poème, pays tribute to one of the earliest experimental sound films, Jean Cocteau's Le Sang d'un poète (1930). It sets up a certain expectation (as nearly all subsequent chapter titles are intended to do), conjuring a reminiscence followed by my personal, poetic spin-off (so to speak).

---------

`Le Ballet monotonique refers to Fernand Léger's Le Ballet mécanique (1924), utilizing a soap detergent commercial from the 1980s. I quote a shot that is repeated 27 times in the avant-garde film classic, of a laundress who walks up a stairway from the river Seine, carrying her washed laundry. I would describe `Ballet monotonique as a rendering of house wives caught in a cage built up of stairs, subject to the tedium of their daily routine (and actresses caught in a prison of repeated takes).

---------

`Cinema of Distraction is a kind of continuation of `Le Ballet monotonique, a handful of `before-and-after shots. The title itself is yet another playful allusion to Gunning's Cinema of Attractions.

---------

`Cubist Cinema _2: Rough Sea at Nowhere

One of my all-time favorite films is Rough Sea at Dover by Birt Acres and Robert W. Paul, shot in 1895 and premiered on Januar 14, 1896 at the `Royal Photographic Society in London. It is to be found on the widely distributed DVD Early Cinema Primitives and Pioneers released by the BFI (hence my hope that a lot of people might have seen the film and get the reference). It shows a) surprisingly enough, a rough sea at Dover, and b) the fascination of the new motion picture medium at the turn of the century. Once you've seen Rough Sea at Dover and realize this film really and deeply fascinated the audience of its time, you can understand the fascination of the suddenly moving image in its day. In my film you get some `rough see through a cubist lens...

---------

`Cubbhist Cinema _3: The Path is the Goal

(Natura morta with Tulips, Guitar, Pork Roast and My Wife in the Bush of Hosts)

Another chapter title that refers to Standish D. Lawder's influential book, The Cubist Cinema (New York 1975). Meanwhile it also represents a playful allusion to the buddhist saying that the path is the goal. It is based on a commercial for stockings. We see a woman running across a meadow over and over again, seemingly without a goal she could ever attain. The imagery makes use of common motifs in cubist paintings (mainly Braque and Picasso), and playfully refers to that wonderful record by Brian Eno and David Byrne, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1981) one of the best pop records of all time. I inserted some Brakhage-Mothlight bushes into the meadow, some coffee party hosts, some `dead nature in the form of cooked food and I got my lady running.

---------

`La Femme à la tête de caoutchouc is of course a playful reference to Georges Méliès' well-known L'Homme à la tête de caoutchouc (The Man with the Rubber Head, 1901): Méliès pumps his head up (with the help of a hidden panning shot) until it explodes. In our case, the pump simply stops working.

---------

`La Femme orchestre also refers to a Georges Méliès film, his celebrated L'Homme orchestre (The One Man Band, 1900), in which Méliès utilizes seven superimpositions to conjure the illusion that he is playing all the instruments. In my film, the orchestra is not presented in a synchronic manner but rather diachronically...

---------

`Deux minutes de cinéma pur is an hommage to that milestone of early avant-garde cinema, Cinq minutes de cinéma pur (1926) by Henri Chomette. This chapter represents my version of a pure cinema. You might also call it an `unintentional cinema, which is as pure as you can get a wink to John Cage.

---------

`Départ de Jérusalem en tracteur is another hommage of mine to the Lumière brothers. It refers to Départ de Jérusalem en chemin de fer (Leaving Jerusalem by Railway, 1897) which I believe shows one of the first panning shots in film history. At the same time it renders a ghost ride in reverse: The camera was mounted onto the back platform of a rail car. The camera starts rolling, the train starts moving and the viewer is leaving Jerusalem (also to be found on that BFI-DVD Early Cinema - Primitives and Pioneers). Well, in our case we are leaving the film, after 25 minutes and 10 seconds. Not with a train, but with a tractor.