A Masque of Madness (Notes on Film 06-B, Monologue 02)

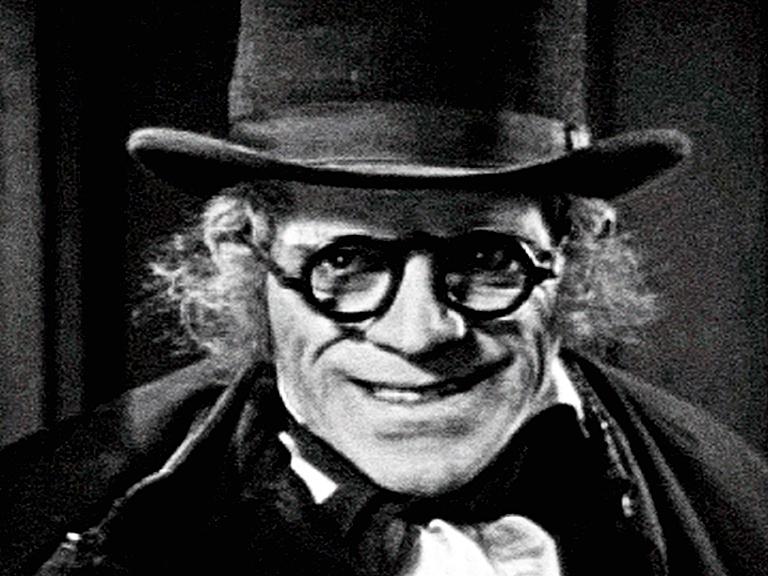

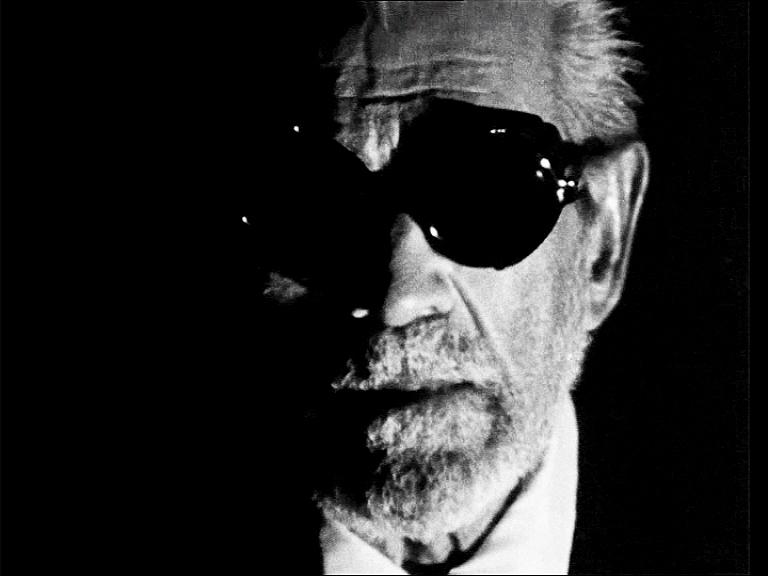

For film scholar Noël Burch, film history begins with a “Frankenstein-like dream” of control: the film medium dismembers animated life into dead fragments to then assemble and reanimate them under its own power. Norbert Pfaffenbichler has put together his own found-footage monster from all of the accessible film appearances of the actor Boris Karloff, who rose to fame in 1931 as Frankenstein’s monster. As already in the previous partner work, A Messenger from the Shadows (starring Lon Chaney), Pfaffenbichler’s re-montage of a film life radiates both analytical interest and a nimble pleasure of association. A Masque of Madness follows the path through five motion picture decades of Karloff—as supporting actor in silent films, star in talking pictures, and television host. The film gathers, in the necessary glory, the ever same rituals of horror film and gestures of exotic danger. But it also exposes the tracks that history has left behind in them—especially the two world wars, and the technological advances.

Time after time, Karloff has to work through the Frankenstein-dream of synthetic life—as Promethean creator and enslaved creature in one and the same person. In this way, Pfaffenbichler reports on not only the career of an outstanding actor, who never managed to escape his most iconic creation, but also his own lab studies on film syntax: The alchemy of continuity editing creates a mirrored gallery of Karloffs stalking one another, which is just as counter logical as it is visually plausible. After the work on silent movie star Chaney, in this film, also the play with the original sound is pleasurably shaping. Rhythmic cuts allow diverse film machines to make music with one another, and Frankenstein’s monster dance to the instrumental accompaniment of a host of Karloffs. “They won’t come to learn, only to stare,” complains the mad scientist after another horrific experiment. Also in this entry in his Notes on Film, Pfaffenbichler decidedly leaves behind the distinction between staring and learning.

(Joachim Schätz)

Translation: Lisa Rosenblatt

Norbert Pfaffenbichler proposes a tragicomedy starring one of Hollywood’s most famous figures, Boris Karloff – and him only. But it is not a collage: it is a show of virtuosity in raccord editing, in mastering the rules of classical decoupage, in shot-reverse shot editing, in dialog editing. It may sometimes look facile, but just think of the research it implies. It is a lesson in classical film narration, and when the editing includes kaleidoscopic and video color effects, it keeps in sync with the history of cinema that Karloff here embodies and with the hallucination the “character” is subject to.

(Marie-Pierre Duhamel)

Locarno 2013. The Question of Vintage. (Article)

Written by Marie-Pierre Duhamel

Following up on his series "Notes On Film", artist/filmmaker/theoretician Norbert Pfaffenbichler proposes a tragicomedy starring one of Hollywood´s most famous figures, Boris Karloff—and him only. The film is composed of shots from Karloff taken from his career in cinema and television—as ages, styles, and even genders, all blend into one narration.

The director himself describes it best:

"In this feature length experimental film the British actor Boris Karloff (1887 - 1969) embodies approximately 170 different characters. An acting career spanning 50 years (1919 - 1969) is compressed into one mind fucking movie. The protagonist experiences a schizophrenic horror trip in which he faces only versions of himself in different masks, at different ages, of different genders and races. Karloff started his career in the silent era and continued working constantly until his death, so one can witness the aesthetic and technical developments of the medium in one single film. All in all he appeared in more than 200 films, TV-series and -shows of almost every genre. The range of quality of these productions could not be greater. He played in unforgettable cinematic masterpieces and worked for directors like John Ford, Howard Hawks, Douglas Sirk, Peter Bogdanovich or James Whale but also appeared in a series of Low-Budget-Horror-movies and cheap TV shows. This nightmarish concept movie is an homage to a great actor and also a weird film history lesson."

Pfaffenbichler´s work is not a collage: it is a show of virtuosity in raccord editing (Boris opening a door from which Karloff emerges), in mastering the rules of classical decoupage, in shot-reverse shot editing (Boris looking at Karloff), in dialog editing (Karloff answering Boris). It may sometimes look facile, but just think of the research it implies. It is a lesson in classical film narration, and when the editing includes kaleidoscopic and video color effects, it keeps in sync with the history of cinema that Karloff here embodies and with the hallucination the "character" is subject to. Pfaffenbichler may call it a "concept movie", yet the film is far from being a strictly theoretical piece. The art of the actor, his face and voice, his irresistible lisp, his elegance and sad eyes transcend masks and make-ups, growls and calls: what the film builds up is a tragedy (with its comedy moments as in the best classical tradition), in a complex topography of cinematic spaces (castles and underground caves, apartments and labs) and with a sense of hellish fatality in time and repetition.

A Masque of Madness is not "cultural", it is cultured, in its ability to escape the cinephilic quiz in order to produce a vision, and to reveal a secret story running ill-noticed inside cinema. Karloff is the monster and the monster´s victim, a portrait of 50 years of madness, in which Pfaffenbichler identifies some themes (war, oppression of the weak, colonialism, criminal science). Fifty years of the death drive; Karloff as mankind; cinema as psyche.

From Pfaffenbichler´s work emerges a cinematic Creature that should be called cinema itself: infinity of the possibles, ubiquitous, doubling, transforming the mutation, constructing imaginary spaces, contiguity of diverse times. The "madness" of the multiple Karloffs comes from an everlasting suffering—being both a tortured creature and its tormentor—leading to a quest for mutation (through experiments, machines, thunder and lightning, chemistry) that produces danger and risk (fear and horror).

Human "evil", the co-existence in one creature of all moral and amoral states, as represented by the editing. With seriousness and humor, the film takes up an old challenge: to dig up stories in the "already filmed" without looking for anything "new" (a delusion) but for something deep. Between the pioneer challenge of an Alberto Grifi (to force Hollywood fiction to make its own auto-criticism) and Pfaffenbichler´s efforts, a fever of technology and of the omnipresence of images has spread, allowing everybody to show off his (possibly) good ideas through the editing of existing film or video material. Basically putting together an image with another which resembles it (analogy) or could be considered its opposite (counter analogy). Images boiled and re-boiled in the same electronic kettle, resulting mostly in tautology (this is—or not—like that). While neither Grifi (at the time) nor Pfaffenbichler (today) ignores that each shot is pierced through by a double line: that of history and mise en scène. This is the source of Pfaffenbichler´s fiction. In his editing room, he may well be a sort of shaman (or be "shaman-ized" by his own meticulousness) who would gather stories (or, who knows, announcements) until now hidden in the shots (le plan), the films, and the tribulations of the actor. The directors of the original films are here convened not as the makers of individual films, but as the makers—and instruments at the same time—of a common story: a more secret one, organic to their work yet left in the unconscious, a collective story that can be brought to light only by the (re)creation of this one creature´s destiny.

Published on 20.08.2013: https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/locarno-2013-the-question-of-vintage-part-3-norbert-pfaffenbilchers-a-masque-of-madness-notes-on-film-06-b-monologue-02

"A Masque of Madness": SIFF Review - hollywoodreporter (Article)

SEATTLE — A piece of experimental cinema recalling some of Christian Marclay´s obsessive compilations of Hollywood moments, Norbert Pfaffenbichler´s A Masque of Madness crafts a feature-length work out of clips from the long and varied movie career of Boris Karloff. More conducive to single-sitting viewing than, say, Marclay´s 24-hour The Clock, it is a scrappier, less polished but more personal creation. Likely to attract the curious at fests, it has limited commercial appeal; but anyone who can watch it without being moved to dig through the DVD archives to revisit a Karloff gem or two might deserve to have his cinephile card revoked.

Subtitled Notes on Film 06-B, Monologue 02, the unusual work is broken into sections that are each labeled "Chapter One". Themes for each are loosely defined but compelling on an intuitive level -- here, we are treated to an assortment of mad scientists, there, a string of dramatic entrances or scenes involving animals. Clips from different eras are jammed together, and the sources range wildly in quality -- some scenes are even taken from foreign-release prints in which Karloff´s voice has been dubbed by another actor, with English subtitles below.

We almost never see another person´s face onscreen. Edits are made so that Karloff often appears to be having conversations with different versions of himself -- cuts match up surprisingly well at times -- or enacting more complicated dramas. "I´m a musician ... I´ll show you", one character says, and then three musical clips from different films are woven together in a discordant mess that tortures its one-person audience, who is shackled so that he cannot escape the recital.

The listener is Frankenstein´s monster, who makes many appearances here but doesn´t dominate the film. Other monsters creep through scenes, from Jekyll´s nemesis Mr. Hyde to less supernatural villains (one yearns for more of The Mummy´s Imhotep), but the actor´s most famous creature is an excellent foil in sequences involving more aristocratic, mortal characters. (Though the film incorporates some truly left-field entries in Karloff´s filmography, from a role he played in drag to the puppet he voiced in Rankin/Bass´ delightful Mad Monster Party, it ignores his role as Dr. Seuss´ Grinch.)

The editing is often faster than one might want, plowing through a dozen anonymous B-movies before it lands on a collection of scenes that lend themselves to one of Pfaffenbichler´s rhythmically repetitive set pieces. The filmmaker does let his star stretch out once or twice, as when he uses a longish speech from The Black Cat as the soundtrack for scenes of eerie, empty halls. (Bela Lugosi, Karloff´s costar in that and several other films, remains a felt but unseen presence.)

The closing credit scroll, which lists not the movies used here but only their directors, reminds us of the array of filmmakers Karloff worked with, including not just those associated with horror, like James Whale and Jacques Tourneur, but others from John Ford to Douglas Sirk. To that list we can now add an Austrian multimedia artist, whose loving film rescues so many of those collaborations from the scrap heap of genre film history.

by John DeFore

A Masque of Madness (Notes on Film 06-B, Monologue 02)

2013

Austria

80 min