Atelier d´Expression

In Friedl vom Gröller´s cinematic art, a heavily de-centered movement occurs. In her films, she shifts the captious power relations between the people depicting, the camera, and those depicted in the event of the encounter. As a living field of conflict and exchange in ever new constellations, she makes this contact zone visibly and tangibly not secured.

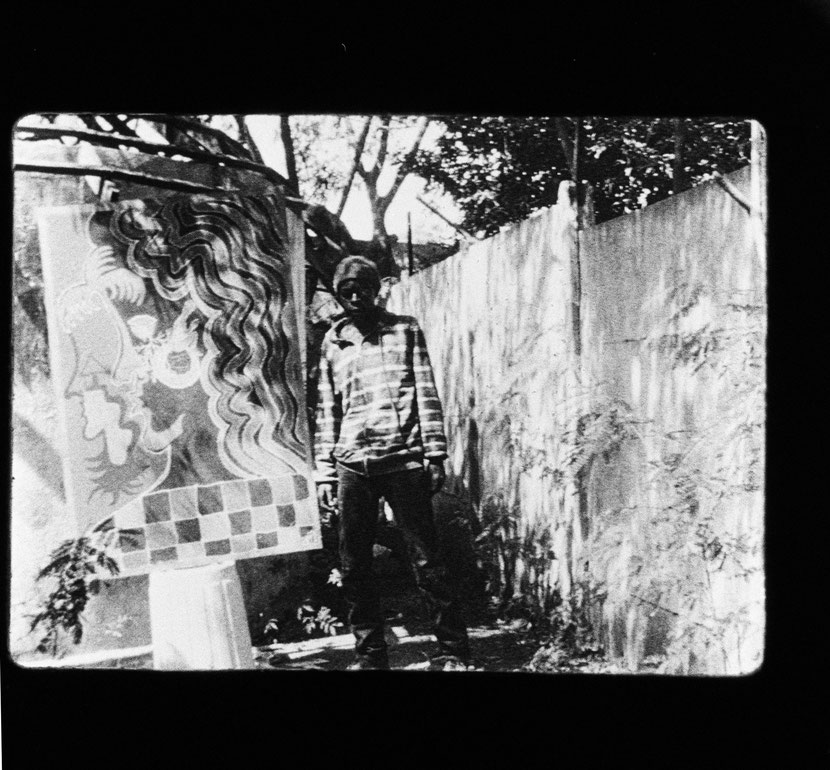

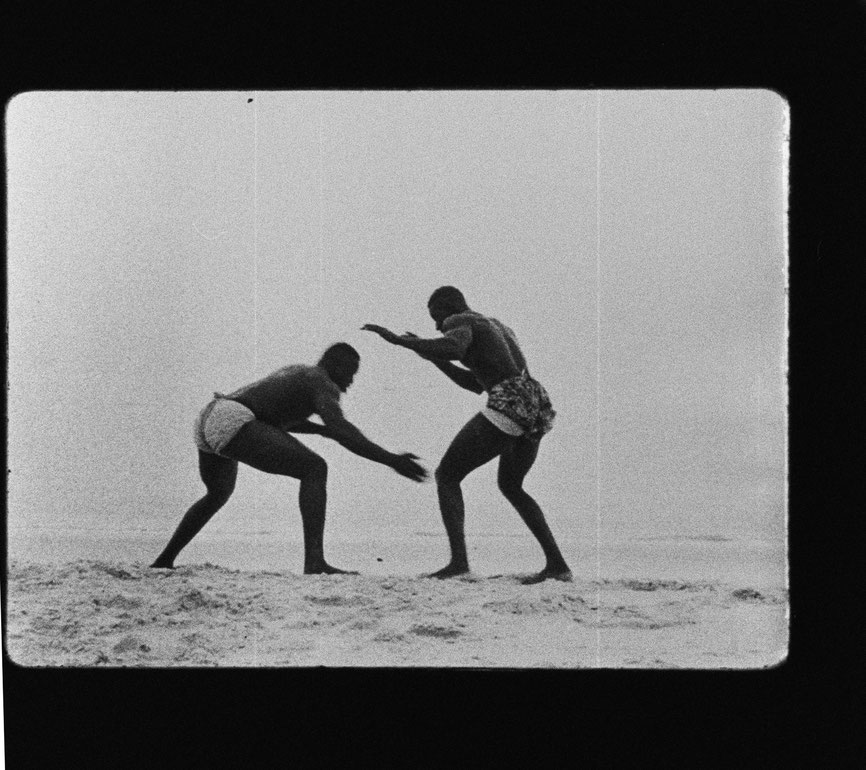

Traveling with a similar position in mind, she undertook a further journey to Senegal, to Dakar, and met seven artists there in the Atelier d´ Expression - a workshop space on the grounds of the psychiatric department of the clinic in Fann near Dakar. The filmmaker portrayed them individually with their works, in many cases based on their own instructions, and frequently stepped back, leaving the portrayed individuals alone with the film camera. Omar N´ Diaye, who is deaf, painted a picture: a leg with a bare foot, which a saurian has bitten into, hatches from a cracked, longitudinal egg shape and a moon head watches, empty-eyed. The artist gazes into the camera and explains the image in sign language, and a further work: a clay figure as portrait of a musician. Another image, a huge gestural, dripping painted eye ornament, the artist close up, his deep gaze, a face. Then, an entirely different type of art breaks in: lutteurs sénégalais, wrestlers, whose demonstrations are charged with conflict and wizardry. They present their virtuosity in the sand on the beach. First, they stand there for the camera and then fight; and our story of asymmetrical power relations and the camera gaze haunt us. Thanks go to the artists: gan-JAH, Djim, Ousmane Diop, Omar N´ Diaye, Tapha, Thierno, and Papis; and special thanks to the lutteurs sénégalais. (Madeleine Bernstorff)

Translation: Lisa Rosenblatt

Friedl Kubelka: Atelier d´Expression (Dakar) / DE

CAMERA AUSTRIA

Spielerische Gegenbewegungen

Stellen Sie sich folgende Situation vor: Man lädt als Kuratorin eine Künstlerin zu einer Ausstellung ein und muss feststellen, dass die Künstlerin ein Netz subversiver Praktiken aufspannt, das sowohl die gängigen Mechanismen der Produktion von Kunst als auch die von Ausstellungen durchkreuzt. Wie verbindet man diese konträren Bewegungen? Im Hinblick auf die Durchkreuzung von Mechanismen der Produktion von Kunst lohnt eine Verschiebung des Blicks auf das Werk der Künstlerin und ihre Form des Arbeitens. Was aber die Durchkreuzung von Mechanismen der Produktion von Ausstellungen betrifft, sollte man eines tun: Offenheit zulassen. Es lohnt sich, nicht alle Enden eines Projekts vorab zu kennen und neue Wege zu finden.

Die Ausstellung—»Friedl Kubelka: Atelier d’Expression (Dakar)« stellt die neueste Arbeit der Künstlerin vor. Die Reflexion über ihre eigene Rolle als Künstlerin, die mit der Entscheidung verbunden ist, das bisherige fotografische Werk zunehmend den Systemen des Kunstmarktes zu entziehen, fällt zusammen mit Kubelkas Beschäftigung mit Menschen, die künstlerisch tätig sind, jedoch abseits des herrschenden Establishments stehen. Diesen sogenannten »Outsidern« und ihrer Kunst ist die Ausstellung von Friedl Kubelka gewidmet. Sie besuchte das Atelier d’Expression in Dakar, eine psychiatrische Einrichtung im Senegal, die den Patienten unter anderem künstlerisches Arbeiten ermöglicht. Die Ausstellung zeigt Porträts der Patienten. Ergänzt werden diese Arbeiten um Werke ihrer Akteure aus dem Senegal. Sie nehmen in der Ausstellung einen wesentlichen Platz ein und werden in einer von der Künstlerin initiierten A(u)ktion zugunsten der Künstler-Patienten versteigert. Doch auch die eigenen (Reise-)Erfahrungen und die unterschiedlichen Ebenen der Begegnung mit der Stadt Dakar und ihren Strukturen erhalten hier Sichtbarkeit.

Die Arbeit und die Ausstellung verlangen unterschiedliche Zugänge.

Arbeit am und gegen das Bild: Hinter jedem Bild wartet ein anderes—Zum einen legt Friedl Kubelka eine eigene Arbeit vor, die sich klar mit dem Werk verbinden lässt, so wie wir es von ihr bisher kennen: eine Arbeit über eine Kontaktnahme, in der zwei Personen ein Verhältnis begründen, getrennt durch die aufnehmende Apparatur, verbunden über Blicke in und durch die Kamera.

Obwohl ein großer Teil des Werks von Friedl Kubelka die Arbeit am Porträt ist, ist ihre künstlerische Methode immer auch eine Arbeit gegen das Porträt. Denn Kubelka arbeitet konstant gegen die Vorstellung des einen, gültigen Bildes. Ihre Stunden-, Tages- oder Jahresporträts sind bis hin zum tausendteiligen Porträt (»Tausend Gedanken«, 1980) zuerst Zeitschnitte im Raum der Begegnung zwischen der Künstlerin und ihrem Gegenüber, sie erzählen von einem Spiel zwischen Nähe und Distanz, von Annäherung und Entfernung oder sogar Entzug. Vielleicht erzählen sie sogar mehr von der Performanz der Begegnung, als dass sie ein Bild abgeben. Gerade in den Filmen zeigt sich das manipulative Potenzial, von denen ihre Porträtsitzungen durchzogen sind. Die Künstlerin begegnet ihren Akteuren mit Witz, Hingabe, manchmal auch mit Kälte. Die Bilder, die entstehen, funktionieren als Befragungen über einen Status sowohl der abgebildeten Person und zugleich des Bildes, der permanent in Bewegung ist. An unausgesprochene Normen rühren und sie berühren ohne diese gewaltsam zu brechen – dies ist die ungemeine Stärke wie auch die Verletzbarkeit dieses Werkes, das nicht als dokumentarisch zu bezeichnen ist, sondern am Ereignis des Bildes arbeitet.

In den aktuellen Porträtarbeiten, die die Patienten der psychiatrischen Abteilung der Klinik Fann (Dakar) zeigen, war es der Künstlerin wichtig, die Integrität des Gegenübers zu wahren, und Momente der Entgleisung, die in ihrem Werk immer auch aufscheinen, auszuschließen – und ihr Gegenüber gerade (oder wieder einmal!) nicht den Erwartungen entsprechend zu zeigen. Wir sehen hier keine »Outsider«. Diese auf der Hand liegende Zuschreibung greift nicht. Ihre Protagonisten sind ernst und un(an)greifbar. Sie geben durch ihren Ausdruck oder ihre Posen keinen Hinweis etwa auf eine (ihre) identitäre Störung. Zuweilen zeigen Utensilien wie ein Pinsel ihr Selbstverständnis als künstlerisch tätige Menschen an. Ansonsten sind wir – wie der Künstler Papis (Babacar Gaye), dessen Gesicht durch das Gras, in dem er liegt, weitgehend verdeckt ist – allein gelassen im Gestrüpp unserer diffusen Vorstellungen von den Menschen, denen Friedl Kubelka im Senegal begegnet ist.

Zum anderen erzählt die Ausstellung von unterschiedlichen Erfahrungsebenen, die der Reise in ein Land geschuldet sind, das eine Fülle von Projektionen und Zuschreibungen provoziert. Als offensiv nicht souveräne Beherrscherin des durchquerten westafrikanischen Raumes arbeitet die Künstlerin mit den inneren und äußeren Widersprüchen, die sie durch das Land führen, und lässt sie in Fotografien von Architekturen und Stadtstrukturen, von ihren eigenen verführerischen Schönheiten und tatsächlichen Abgründen sichtbar werden. Entstanden ist eine Arbeit, die zwar politisch gelesen werden will, in der sich aber in der Betrachtung immer wieder die persönliche Erfahrungsebene ganz klar dazwischen und nach vorne schiebt. Das produziert Störmomente. Wenn wir nur das Wort »Afrika« hören, sind wir alarmiert. Wir verlangen wir nach Klarheit, nach Objektivität, nach Wissen, Information, Umsicht, nach Grundsätzen. All das muss sich mit der Arbeit einer europäischen Künstlerin, die sich in diesem Raum bewegt, mitteilen. All das mag die Künstlerin interessieren oder wissen, für ihre Arbeit am Bild aber spielt diese Erwartung überhaupt keine Rolle. Kubelka schiebt die gängigen, die existenten Projektionen gerade nicht beiseite, um einem zurechtgerückten Bild zuzuarbeiten, mit dem sich im besten Falle verobjektivierbares Wissen mitteilt oder ein unangreifbares Werk aufbaut – sondern zeigt sich mit ihren Bildern als schuldig/unschuldige, als wissend/nicht-wissende, offen-neugierige/angst-und schamvoll Reisende und Fremde. Nur eines ist zentral: Alles ist erlaubt.

Durchbrechen etablierter Verwertungskreisläufe: unverkäuflich/verkäuflich—Entstanden sind diese Arbeiten aus den Impulsen einer kontinuierlich arbeitenden Künstlerin – ohne die zwingende Absicht einer Veröffentlichung, etwa in Form einer Ausstellung. Man könnte nun sagen, Kubelkas Werkbegriff sei persönlich. Und in der Tat wird immer wieder deutlich, wie sehr die Ebene der zutiefst persönlichen Erfahrung sich im Prozess des Machens in die Arbeit einschreibt und genau hier ihre Qualifizierung sucht. Als eine Form der konstanten Selbstbefragung. Zugleich aber ist diese Vorstellung des Arbeitens »für sich« eminent politisch: als eine Form des Insistierens auf die Autonomie als künstlerisch tätiges Subjekt, abseits von Verwertungskreisläufen, in die die Arbeit eingespeist wird, in dem sie öffentlich wird.

Im Falle der jetzt gemeinsam erarbeiteten Ausstellung nutzte die Künstlerin die Einladung an sie, um die Mechanismen der Produktion von Ausstellungen provokativ zu durchkreuzen – indem sie »fremde« Werke in die Ausstellung schleust: Es sind Werke von Menschen, die künstlerisch tätig sind, ohne dass diese selbst einen Raum für die Präsentation ihrer Arbeiten in unserem Kontext je finden würden. Hat die Künstlerin also einerseits für sich selbst ihre Unverkäuflichkeit beschlossen, so nutzt sie andererseits ihre Einladung in einem institutionellem Kontext, um einen Raum für diejenigen zu erschließen, die kaum Sichtbarkeit für ihre Arbeit erzeugen können. Damit ist die Subversivität ihres Handeln aber noch nicht zu Ende: Teil der Ausstellung ist nicht nur Friedl Kubelkas Idee, »fremde« Werke in die Ausstellung zu bringen, sondern mehr noch: diese in einer von ihr initiierten A(u)ktion zu veräußern, sie offensiv als »verkäuflich« zu markieren. Um auch diesen Arbeiten einen Wert zuzuschreiben, ein Wert, der sich – ja – auch in einem Preis niederschlagen kann. Um den Künstler-Patienten einen Lohn ihrer Arbeit zuzusprechen. Und um konkret zu werden und das Atelier d’Expression im senegalischen Dakar und ihre dort arbeitenden Künstler nicht nur ideell zu würdigen.

inside/outside: Sprechen über die Kunst von AußenseiterInnen¹ —Betrachten wir die in der Ausstellung vorgestellten Werke der senegalesischen Künstler als Werke von Patienten, die eine psychiatrische Einrichtung besuchen, können wir sie im Kontext der Debatten um sogenannte »Outsider-Kunst« verorten. Aber kommen wir damit weiter?

Heute wird die »Outsider Art« als fester Stilbegriff verwendet, so, als ob er analog zu anderen Stilrichtungen tatsächlich einen spezifischen Stil bezeichnen würde. Wer sich jedoch eingehender beschäftigt, wird sehen, dass die Werke der verschiedensten KünstlerInnen, die hier subsumiert werden, kaum miteinander verbunden sind. Was also kann »Outsider Art« tatsächlich sein? Denn: Sie ist kein Stil, sie umfasst keinen spezifischen geografischen Raum, sie steckt keine klar definierte Zeitspanne ab und sie bezeichnet auch keine bestimme künstlerische Ausrichtung.

Die Frage ist also, ob eine Kategorisierung im Sinne der Outsider-Kunst den UrheberInnen der Werke zum Beispiel zu (neuer) Würde verhilft? Oder aber ob sie umgekehrt diese erneut ausgrenzt oder gar bevormundet? Klar ist, dass die Anerkennung der »Außenseiterkunst« eine Geste der Befreiung darstellt, die mitgeholfen hat, einzigartige Werke zu entdecken. Im Falle der von Friedl Kubelka in den Kontext dieser Ausstellung geschleusten Werke lohnt die Einlassung, dass Kunst an unerwarteten Orten entstehen kann, und dass ihre Bedeutung nicht zwingend davon abhängt, ob ihre UrheberInnen die Kunst und ihre Geschichte – welche Geschichte der Kunst auch immer – kennen. Was zählt, ist das Werk, dessen ästhetischer Reichtum und Komplexität, die Gedanken und Bezüge, die es formuliert, dessen Präzision und was es riskiert. Die Frage nach »inside« oder »outside« ist unbedeutend und hinderlich, da sie ein Verständnis verunmöglicht. Traditionell werden die Arbeiten der »Art Brut« als Beispiele »ursprünglicher« Kunst gehandelt, außerhalb von Zeit und Geschichte stehend. Dabei erzählen sie alle – oft mehr als uns lieb ist – »von einer Welt, die wir zu kennen glauben. Hinter vordergründiger Weltabgewandtheit breiten sie verdrängte Realitäten aus, entfalten unterdrückte Sehnsüchte, fordern uneingelöste Versprechen ein und erinnern an übergangene Ungerechtigkeiten« (Daniel Baumann). All das sprechen die hier mitausgestellten Werke an. Mit der Ausstellung von Friedl Kubelka verlassen wir das Gehege, in das die »Outsider Art« eingefriedet wurde, und lassen uns auf ihre Werke als Kunst, und nur als Kunst, ein. So stellt sie die Künstlerin Friedl Kubelka uns vor. Und genau so, wie Friedl Kubelka den Künstler-Patienten Namen gegeben hat und sie als schöpferische Persönlichkeiten in ihren Fotografien zeigt, so können wir versuchen, ihnen und ihren Werken frei und unbefangen zu begegnen. Ob das gelingt, ohne sie als Fremdkörper zu stilisieren, oder zu einem Symptom verkommen zu lassen, bleibt – nicht nur in diesem Projekt, sondern überall dort, wo wir mit sogenannter »Outsider-Kunst« in Berührung kommen – offen.

… auch noch Afrika!—Wir werden dabei nicht umhin kommen, unsere europäischen Augen auf die Bilder zu heften, und die Werke mit dem geschulten Blick unserer kunsthistorisch-europäischen Bildung abzugleichen – wohl in dem Wissen, dass diese Werke in einem Kontext entstanden sind, von dem wir nicht wissen, auf welchen ästhetischen Vorstellungen er gründet. Wir können versuchen, sie in den Kontext ihrer Entstehung zu stellen, sie ggbf. kreuzen mit unserem Wissen um die koloniale und von Rassismen durchzogene Geschichte der Beziehungen zwischen Europa und dem westafrikanischen Raum. Okwui Enwezor hat 2001 mit »The Short Century« die Rezeption der afrikanischen Moderne begründet. Ein Gegenlesen der Bilder in unserer Ausstellung mit seinen Recherche- und Forschungsergebnissen mag lohnend sein, und neue Kontexte öffnen – freilich, ohne die für die Moderne typische intrinsische Verbindung von Befreiung und Züchtigung, Idealisierung und Abgrenzung.

Risiko—In einer Zeit, in der die Produktion und das Sprechen über zeitgenössische Kunst von Re-Feudalisierung und Eventisierung durchzogen werden, und in der wichtige Verhandlungsfragen über den Status der zeitgenössischen Kunst erst zur Debatte gelangen, wenn das Establishment oder der Kunstmarkt bereits versorgt sind, ist es wichtig, Projekte wie das von Friedl Kubelka zuzulassen – auch auf die Gefahr hin, dass einige bei einer kritischen Betrachtungsweise vielleicht am Ende dahin kommen, die Grenzen von Institution und Kunstauffassung – wieder – enger abzustecken. Wenn wir aber eine Einlassung wagen, können wir vielleicht eine doppelte Widerständigkeit erkennen, die sich nicht zufrieden gibt mit einem »commom sense«, sondern subversives Denken und Handeln immer wieder neu ermöglicht und dabei in neue Räume vorstößt. Dies ist eine Debatte, die ideologische Fragen berührt. Führen wir sie!

Maren Lübbke-Tidow

¹ Ich danke Daniel Baumann für Hinweise und Gespräche.

Friedl Kubelka: Atelier d´Expression (Dakar) / EN

CAMERA AUSTRIA

Friedl Kubelka:

Atelier d’Expression (Dakar)

Playful Countermovements

Imagine the following situation: a curator invites an artist to participate in an exhibition and then comes to realise that the artist has spanned a web of subversive practices that thwart both the conventional mechanisms of art production and those at play in an exhibition context. How might one connect such contrary movements? In view of this thwarting of mechanisms related to art production, it makes sense to shift the gaze to the work of the artist and her way of working. Yet when it comes to the thwarting of the mechanisms involved in the production of exhibitions, it is crucial to foster openness. It is beneficial to actually not know how each project will end so as to find new paths in the process.

The Exhibition—“Friedl Kubelka: Atelier d’Expression (Dakar)” introduces the artist’s most recent work. Reflection on her own role as an artist, which is related to the decision to increasingly withdraw her previous artistic work from the systems governing the art market, coincides with Kubelka’s interest in people who are engaging in artistic activity while remaining outside the dominant establishment. The exhibition by Friedl Kubelka is devoted to these so-called “outsiders” and their art. She visited the Atelier d’Expression in Dakar, a psychiatric clinic in Senegal, which gives patients an opportunity to pursue, among other things, artistic activity. The exhibition shows portraits of the patients. These works are supplemented by the artwork of those portrayed in Senegal. The latter assumes an essential position within the exhibition and will be sold at an a(u)ction organised by the artist to the benefit of the artist-patients. Becoming visible here, too, are Kubelka’s own (travel) experiences and the different levels of encounter with the city of Dakar and related structures.

The work and the exhibition require different points of access.

Working On and Against the Image: Behind Each Image Awaits Another—On the one hand, Friedl Kubelka presents her own work, which is clearly associated with her previous work as we know it. It deals with an act of contact initiation where two individuals enter into a relationship with each other, separated by the apparatus capturing the situation yet united through gazing into and through the camera. Although a large portion of Friedl Kubelka’s oeuvre involves portrait work, her artistic method is simultaneously always a way of working against the portrait. In fact, Kubelka constantly works against the idea of there being one valid picture. Her hourly, daily, or yearly portraits, all the way to a thousand-part portrait (“Tausend Gedanken”, 1980), are firstly time-cuts in the space of encounter between the artist and the person across from her; they speak of interplay among proximity and distance, of moving towards and away, or even deprivation. Perhaps they even speak more of the performance of encounter than actually presenting an image. The manipulative potential permeating her portrait sessions is especially evident in her films. The artist meets her protagonists with humour, devotion, or sometimes even with dispassion. The resulting images function as surveys of the status of both the person rendered and the image itself, a status which is constantly in motion. Stirring and touching unspoken norms without violently breaching them—this is the incredible strength yet also vulnerability of this oeuvre, which cannot be termed documentary but rather brings forward the image as an event.

In the current portrait works, showing patients from the psychiatric ward of Fann Hospital in Dakar, it was important to the artist to maintain the integrity of her counterpart, and also to preclude the moments of derailment that repeatedly arise in her work—while especially (or once again!) making sure to fall short of expectations towards the represented vis-à-vis. Here we see no “outsiders”. This easily assigned ascription does not apply. Her protagonists are serious and tangible/unassailable. Their expressions or poses give no indication of an identity disorder. At times, art utensils like a paintbrush give an indication of their self-conception as artistically engaged individuals. Otherwise we—like the artist Papis (Babacar Gaye), whose face is largely covered by the grass in which he is resting—are left alone in the thicket of our diffuse conceptions of the people whom Friedl Kubelka came across in Senegal.

On the other hand, the exhibition speaks of different experiential levels owing to travel to a country that provokes a wealth of projections and ascriptions. The artist, as a purposely non-sovereign master of the traversed West African region, works with the inner and outer contradictions leading her through the country, and she lends visual form to these contrasts in photographs of architecture and urban structures, of their own seductive beauties and very real precipices. An artwork thus arose that may beg to be politically read, but in which, during the act of viewing, the personal realm of experience very clearly pushes itself in between and to the forefront again and again. This induces moments of disruption. Even just hearing the word “Africa” alarms us. We demand clarity, and objectivity, and knowledge, information, discretion, and precepts. All this must be conveyed by the work of a European artist who is moving within this space. All this may be of interest or known to the artist, but for her work on the image this expectation plays no role whatsoever. Kubelka expressly does not push aside the common, extant projections in order to arrive at an adjusted image that, in the best case scenario, conveys objectifiable knowledge or establishes an unassailable work. Instead, she presents herself through her images as a traveller and foreigner who is guilty/innocent, knowledgeable/lacking in knowledge, opencurious/full of angst and shame. Only one thing is pivotal: anything goes.

Breaking through Established Cycles of Use: Unsaleable/Saleable—These works originated through the impulses of a continually productive artist—without the definite intent to release the works, for instance in an exhibition format. One could say that Kubelka’s working approach is personal. In fact, it does repeatedly become clear how strongly the plane of very deep personal experience becomes inscribed into her artwork during the creative process, seeking qualification precisely here. As a form of constant self-questioning. At the same time, this idea of working “in and of itself” is already eminently political: as form of insistence on the autonomy as an artistically inclined subject, beyond cycles of use in which the work is engaged, when it becomes public.

In the case of the exhibition jointly developed here, the artist used the invitation to provocatively thwart the mechanisms of exhibition production. She did so by channelling “foreign” works into the exhibition—works by people who work artistically but would themselves never be able to find a place for presenting their artwork in our context. So while the artist, on the one hand, herself decided on the unsaleability of her work, she used her invitation to participate in an institutional context, on the other, to gain access to a space for those who can hardly garner visibility for their artistic work. But the subversiveness of her activity does not end here. It goes beyond Friedl Kubelka’s idea to integrate “foreign” works in the exhibition to actually have them be sold in an a(u)ction initiated by her, thus offensively marking them as “saleable”. With the aim of also ascribing value to these works—value that, of course, is also reflected by a price. With the aim of providing the artist-patients with a wage for their work. And with the aim of becoming more concrete and showing appreciation towards the Atelier d’Expression in the Senegalese city of Dakar and the artists working there in a way that is more than just ideational.

inside/outside: Speaking about the Art of Outsiders¹—If we consider the artwork by Senegalese artists introduced in the exhibition as the work of patients visiting a psychiatric institution, then we can localise them in the context of discourse on so-called “Outsider Art”. But does this achieve anything? Today Outsider Art is used as an established concept of style, as if it actually denoted a specific style analogous to other genres. But those who take a more in-depth look will note that the works by the various artists subsumed here are hardly related. So what might Outsider Art really be? Indeed, it is not a style, it does not encompass a specific geographic area, it fails to delineate any clear time period, nor does it denote a particular artistic orientation.

So the question is whether a categorisation as Outsider Art is even able to imbue the creators of the artwork with a sense of (new) dignity. Or whether it would conversely serve to once again marginalise or even patronise them? Clearly, the acknowledgement of so-called “Outsider Art” represents a gesture of liberation, which has helped to discover unique works of art. In the case of the works channelled into this specific exhibition context by Friedl Kubelka, it is worthwhile to acknowledge that art can be created in unexpected places, and that its meaning does not necessarily depend on whether the originators are knowledgeable about art and its history—

whichever history of art. What counts is the work itself, its aesthetic richness and complexity, the thoughts and references that it formulates, its precision and the risks it takes. The question of “inside” or “outside” is unimportant and debilitating, for it hampers understanding. For example, works of Art Brut have been traditionally treated as examples of “primal” art, existing beyond the confines of time and history. They actually all tell—often more than we would like—°“of a world that we believe to know. Behind superficial unworldliness, they spread out repressed realities, unfold inhibited yearnings, call for promises to be redeemed, and remind of ignored injustices” (Daniel Baumann). The exhibited works speak to all of the above. With the exhibition of Friedl Kubelka, we are leaving the corral in which outsider art has been enclosed and opening ourselves up to their work as art—and solely as art. This is how the artist Friedl Kubelka introduces it to us. And just as Friedl Kubelka has given the artist-patients names and is showing them as creative personalities in her photographs, now we can try to encounter them and their works in an open and unbiased way. Still, it remains to be seen as to whether we will succeed in this without stylising them as foreign matter or allowing them to degenerate into a symptom—not only in this project, but everywhere that we come into contact with so-called “Outsider Art”.

… and even Africa!—We won’t be able to avoid sticking our European eyes onto these images and adjust to the works with the trained gaze of our European, art-historical education—though with the knowledge that these artworks were created in a context in which we are not sure on which aesthetic concepts they are founded. We can try to place them in the context of their origination, that is, to criss-cross it with our knowledge about colonial history, interveined with racism, about the relations between Europe and the West African region. In 2001, Okwui Enwezor substantiated the reception of African modernity with “The Short Century”. A comparison of the photographs in our exhibition with his research results may be well worth one’s while, opening up new contexts—of course, without the intrinsic association between liberation and penalisation, idealisation and delimitation, so typical for modern times.

Risk—During a period in which both the production of and discourse on contemporary art are permeated by refeudalisation and eventisation, and in which the important questions of negotiation about the status of contemporary art are finally arriving at the point of debate, and where the establishment or the art market is already adequately supplied—precisely now it is important to embrace projects like that of Friedl Kubelka. Even giving the danger that some ending up—once again—at narrowing down the boundaries of institutions and the concept of art with a critical view. Yet if we venture an assertion, then perhaps we can recognise a dual sense of resistance that is not content with “common sense”. Instead, it repeatedly enables subversive thought and action, pushing through to new spaces in the process. This is a debate that touches on ideological issues. Let us pursue it!

Maren Lübbke-Tidow

¹ Many thanks to Daniel Baumann for the information and discussions.