Winter in Paris

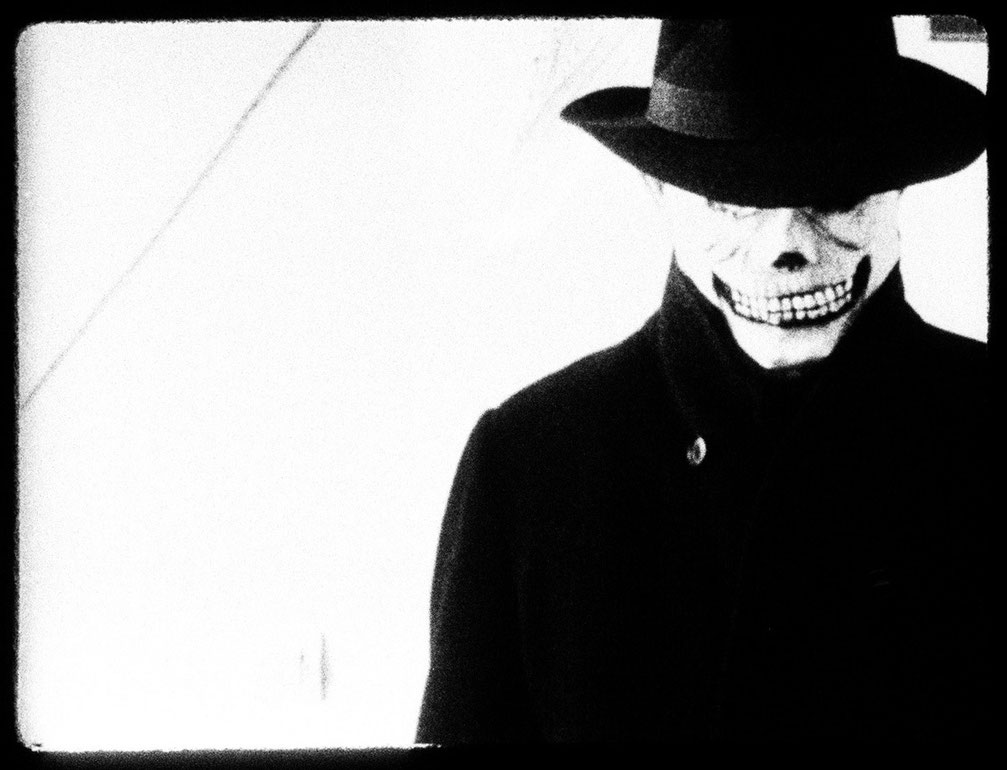

Like another one of her "Paris films"– namely 66, rue Stephenson – Winter in Paris begins with an interior shot – or, to be more precise, a still-life of a window sill. But the camera is not interested in dwelling on motionless matters for long, and with a slow but decisive movement, it finds its way to scaffolding outside, where more exciting matters are to be observed and shown. It briefly appears that the filmmaker has found her visual subject in the geometrical abstraction outside her window. But the film soon changes its register and shifts away from the contemplative language of looking at the verticals and horizontals of steel and a piece of rope gently dangling. A male – fragmented – body of a worker comes into play and becomes the object of female voyeuristic pleasure: upper body in work clothes, legs climbing a diagonal ladder, a behind, strong arms capable of heavy work, robust shoes, a hat, a tool-belt with serious tools. The scaffolding serves as a hinge between inside and outside, and more importantly, as a kind of stage for work, youth, courage and cowboy-like masculinity. After this minimalist "action film" part, a horizontal pan shifts the film back to the interior, gliding over a wall and fleetingly showing an interest in its surface texture before taking a surprising turn to a commonly treated motif in art history. Friedl vom Gröller stages the gruesome-erotic allegory of death and the maiden as worldly and highly personal: an encounter driven by mutual desire – with herself in the end playing the female role as the impishly mischievous woman gazing into the camera. And it is only after this that the film realizes its actual goal, with an emancipatory, unfettered pan to the city, the outside, the expansive view beyond. Taking the most beautiful detours, Winter in Paris realizes a gaze free of restrictive circumspection, an emancipated "open" looking. (Esther Buss)

(Translation: Eve Heller)