under the microscope

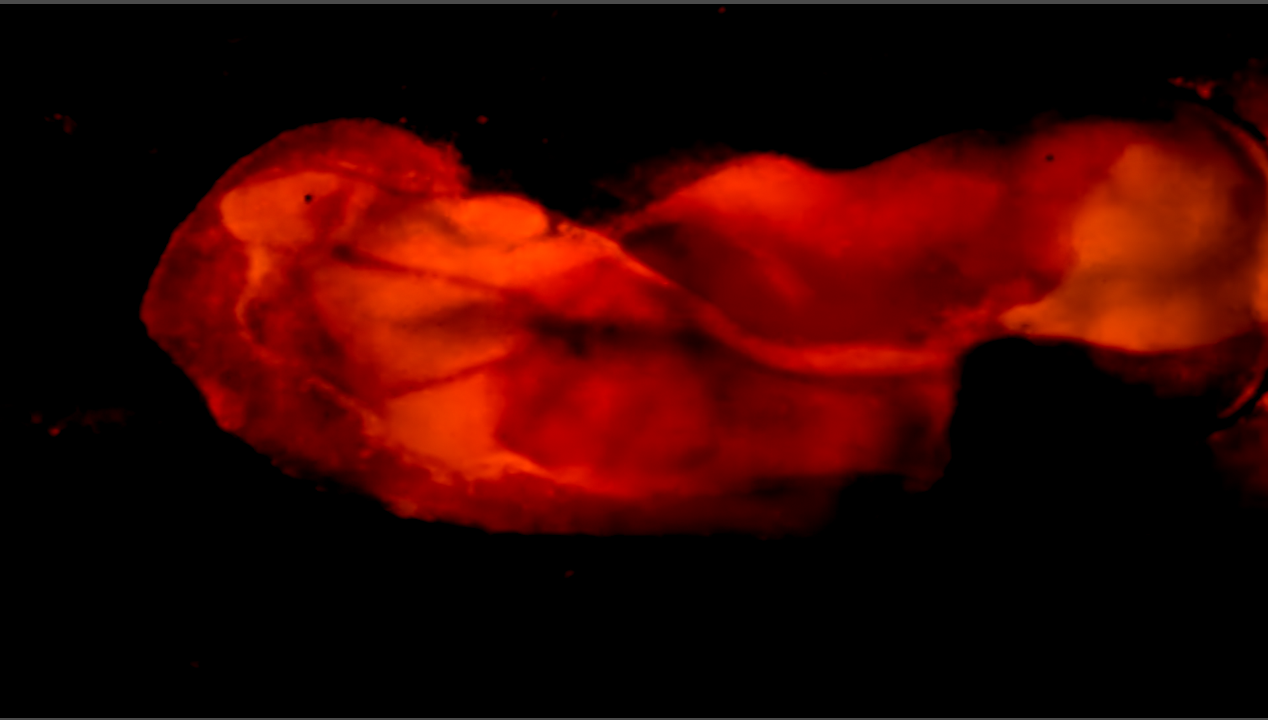

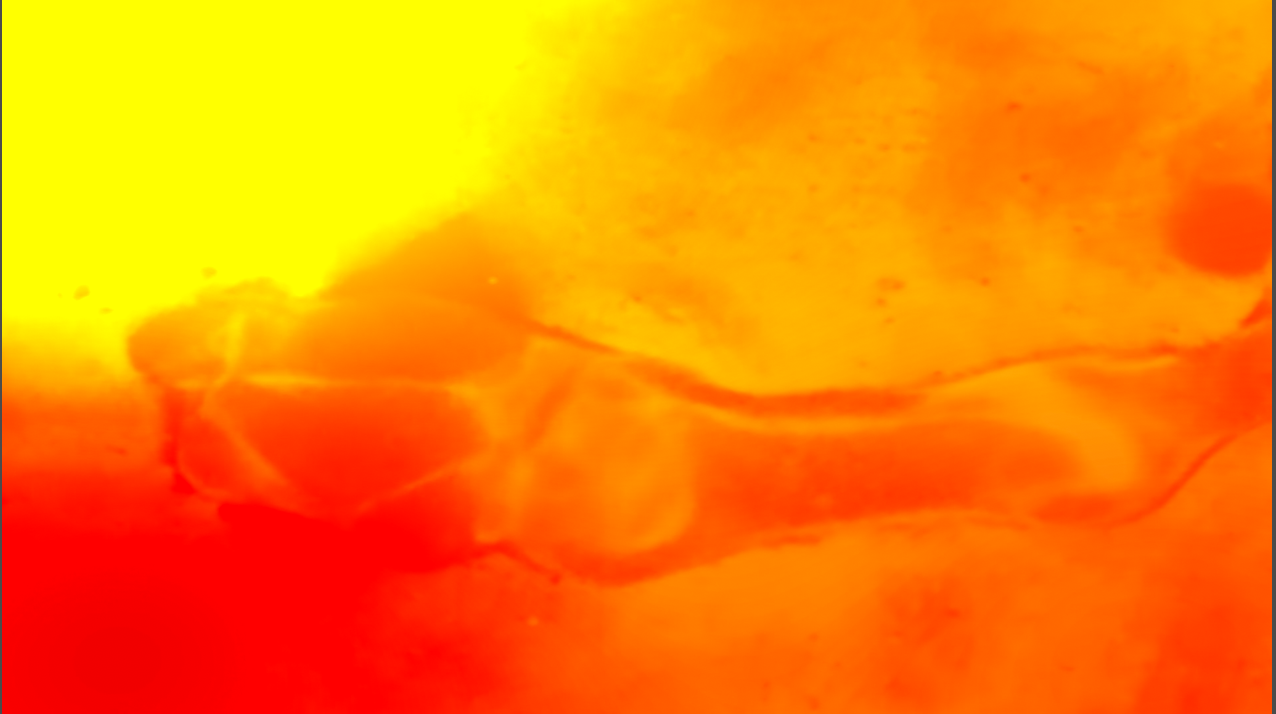

Among the arguments made in favor of cinema as a source of scientific knowledge, the most obvious one right from the start was that film not only records movement, but in many cases makes it perceptible in the first place. Magnification reveals cellular processes; time-lapse and slow-motion effects bring the bursting of pollen and sprouting of flowers up to the scale of human perception. In under the microscope, these and other famous motifs from the history of science films make their appearance. Just as often, however, it is hard to determine just what is pulsating, bursting, or proliferating in the picture. In her glittering remontage of science films from the 1920s, Michaela Grill does not spread out catalogues of motifs, but aims straight at the fascination of these recordings: their value as educational material was never neatly separated from their aesthetic appeal as a pure cinematic spectacle. Discrete forms begin to swarm; seemingly motionless things break out into choreographies. Found nature and technical image processes dance closely entwined. Grill uncovers these visual events and explores their cinematic value through color transformations loosely based on historical tinting, through cross-fading and cutting heightened to a point of flickering staccato, through rhythmic editing of image detail and the speed of movement. In the same way, in the course of the film Sophie Trudeau’s soundtrack changes, from the regularity of clock ticking to driving machine music. Like its source material, the film does not amount to ornamental abstraction, but alternates between recognizable objects becoming alien and illegible forms becoming familiar. Here, photographic reference does not serve as a confirmation of what is already known, but a starting point for exploration. The mysteries of cinematic perception are only just beginning under the microscope. (Joachim Schätz)

Translation: John Wojtowicz

under the microscope

2021

Austria, Canada

7 min