Remote...Remote...

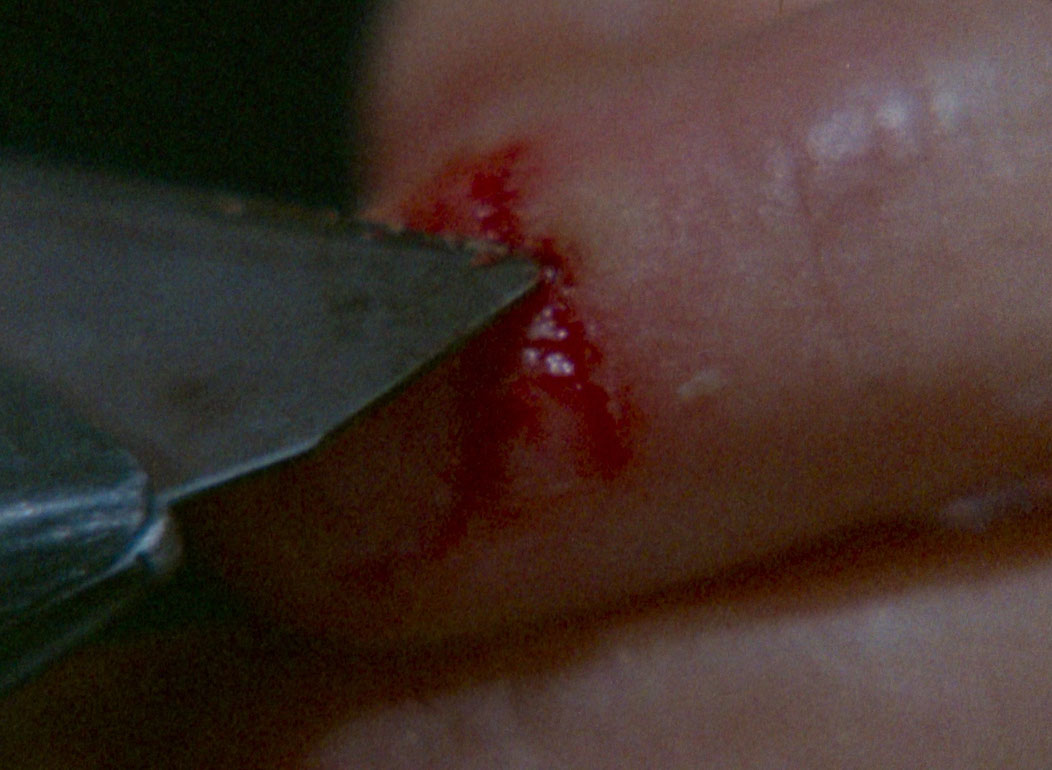

....Remote.....Remote..... is not, as was said, a film about suffering. The actress (the artist) does not suffer. Or does not show. It’s a film about the wound. For the woman mutilates herself, the essence lies in the result: blood. These repeated mutilations cause her to bleed continuously, which she staunches by sucking her reddened fingers. But as the blood continues to flow, she ends up plunging it in a bowl of milk. Red and white. These are the very fluids of femaleness: lactescence (maternal) and menstruation (sexual). But these barbaric weddings are more than a mixture: a metamorphosis. VALIE EXPORT turns milk into blood. And the body into tragedy. (Régis Michel)

Human behaviour in contrast to machines (animals) is influenced by events in the past, as far back as these experiences may lie. Therefore there exists a psychic paratime parallel to the objective time, where the prayers of anguish and guilt, the inability to win, deformations which rip open the skin, becoming aware of oneself, have their constant effects. I demonstrate something which represents past and present. (V.E.)

....Remote....Remote.... was one of the films categorized by a considerable number of women as typifying despicable excesses and extreme violence. People frequently reacted to the film with horror, incomprehension and scorn. In showing emotion, gentleness and sensitivity as female qualities, there was no place for aggression - cutting and violently opening were equated with male behaviour; having to pentrate in order to possess.

When Valie Export shaves and trims herself, the sight of her provokes fantasies, revolving around acts done to the body. Yet there is nothing dreadful about a woman trimming her body, especially in the places where she enhances the glamour imposed on her body by the civilizing influences of the world around her. And the fact that you have to suffer to achieve beauty has always brought a knowing smile to a woman´s lips.

The way in which Valie Export grooms herself however, involves unconventional touching and violation which goes beyond the familiar sight of a woman "harmlessly" doing herself up. This triggered, and continues to trigger, huge defensive reactions among many women. Such a reaction represents the easiest way of emphatically rejecting something that has got right under the skin. No-one is allowed to encroach into the recesses of our private existence, in which the damage suffered and our own self-mutilation remains safeguarded behind a front of normality. (Renate Lippert)

Stefan Grissemann zu ...Remote...Remote... von Valie Export

"MOMA's Best Week Ever. Innovator meets Image Maker in dueling retrospectives", by Ed Halter, Village Voice, New York, February 28th, 2007 (Critique)

A multimedia artist before such terminology even existed, Export created her early films, videos, and performances during Vienna's unique streak of politically engaged avant-gardism in the '60s and '70s known as Aktionism: acting out shocking displays of body-horror within a framework of highly structured formalism. Remote...Remote (1973) is one of the most gruelingly extreme of these early works. In it, Export uses an Exacto knifea familiar if latently dangerous artist's toolto slice away at her cuticles and fingertips, displaying the red mutilation with audience-unfriendly close-ups. Eventually, she mixes the blood from her self-inflicted wounds into a dish of milkan evocative nod to both menstruation and motherhood, stripped down to their most primal symbols. Other works attempted to expand the concept of cinema beyond mere theatrical projection: In Touch Cinema (1968), Export walked the streets of Vienna wearing a box with curtained holes in the front, offering passers-by the opportunity to reach inside and feel her chest: Thus the mainstream movies' enduring obsession with women's breasts becomes reduced to its barest essence in a miniature tactile theater for the hands. (In keeping with her confrontational, proto-punk attitude, one performance of Touch Cinema in Germany instigated a riot that left Export with a nasty head wound.)

In later years, Export reworked these themes into a number of feature films; MOMA will be running two. Her longform debut, the enjoyably primitive Invisible Adversaries (1976), melds a Z-grade science-fiction narrative with disorienting chunks of formal experimentation and strident outbursts of manifesto-spieling; in mashing-up Godardian revolution with exploitation-film seediness, Adversaries foreshadows the similarly low-rent obsessions of New York's No Wave underground. The storylinesomething about an alien race called "Hyksos," their name apparently nicked from a historically mysterious people who conquered ancient Egyptquickly submerges beneath Export's disjunctive agglutination of multimedia set pieces, strung together with an almost Monty Pythonesque absurdity. As in her earlier works, Export places women in situations where they become paradoxically abject and strident, even surreally glamorous. In one dreamlike sequence, a woman walks past everyday Viennese shoppers in a pair of ice-skates, metal blades clanking on concrete with every step. In another, she cuts off bits of pubic hair and glues them beneath her nose, creating create a goofy fascist mustache.

More story-driven but no less disjointed, Export's The Practice of Love (1984) is a feminist reworking of film noir in which a female reporter becomes involved with two hommes fatales while investigating a subway murder. More akin to the deconstructions of Yvonne Rainer or Sally Potter, Practice elaborates on the snooping camerawork of classic Hollywood crime flicks by incorporating an array of modern surveillance techniquestelevision cameras, security video, photography, and live-nude-girl peep shows. Though both Adversaries and Practice lose the tightly focused, evocative power of the director's shorter works, they still attest to why a younger generation of women artists has embraced the fearless Export as a spiritual foremother: She's been name-checked by the electro-feminist band Le Tigre and celebrated by the ladyqueer art-collective LTTR (Lesbians to the Rescue). Even in their ambitious imperfections, Export's films serve up more conceptual heft and adult rigor than most anything seen in the featherweight romper-room of today's gallery world; the fangless nudie shenanigans of Julie Atlas Muz, for example, seem like mere college-party clownage in comparison.

Export translated her art into feature filmmaking, but Kiarostami has gone the opposite route. In addition to arriving in person for a comprehensive month-long Kiarostami-paloozawhich includes rarities such as his pre-Revolutionary featurette The Wedding Suit (1976), a Truffautian tale of three teenage boys, and numerous short subjects made for childrenhe'll premiere a multi-channel installation version of his minimal digital-video feature Five (2004), alternatively titled Five Dedicated to Ozu. The theatrical version of the film consists of five unbroken shots of a seashore; even without story or characters, it proves remarkably captivating, like a perfectly crafted object of contemplationor, conversely, a completely transparent window onto nature. In the gallery, it will show as five looping projections, returning the experience to a closer approximation of its environmental source.

--> village voice