Invisible Adversaries

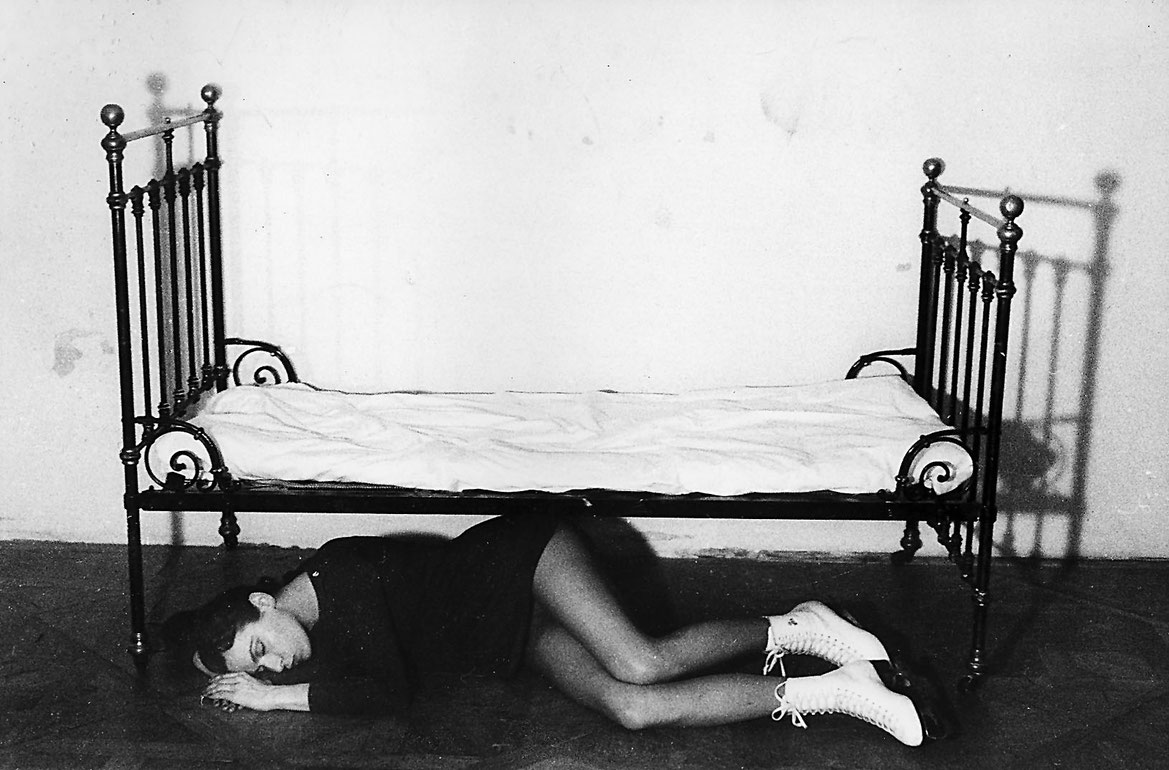

Anna, an artist, is obsessed with the invasion of alien doubles bent on total destruction. Her schizophrenia is reflected in the juxtapositions of long movie camera takes with violently edited montages: private with public spaces; black & white with colour, still photographs with video, earsplitting sounds with disruptive camera angles. Anna uses her body like a map; after a devastating quarrel with her lover, she paints red stitches on herself. Watching their scenes together, we realize how seldom, if ever before, the details of sexual intimacy have been shown in film from the point of view from a woman. Export privileges rupture over unity and never settles for one-dimensional solutions.

(Artforum, Nov. 1980)

Anna, a photographer and video reporter in Vienna, hears a radio report about an invasion of invisible aliens – the Hyksos – who intend to take over the Earth and its inhabitants. “But the aspects of VALIE EXPORT’s film that are of interest to us come not only from the theme of a schizophrenic young woman and her relationship with a paternalistic man, but also from the aesthetic she developed simultaneously. The film does not submit aesthetically to a clean division between a normal, objective surroundings and abnormal, schizophrenic distortion and projection. It neither filmically separates the projections and dreams from their environment in quasi- bjectivity nor does it lose itself to a depiction of the woman’s subjective point of view by pretending to assume it for the purpose of telling the story. On the contrary, the film takes its aesthetic from the very fact that it includes the various levels.”

(Gertrud Koch)

Roswitha Müller: VALIE EXPORT. Bild-Risse (Auszug) dt.

(...) Die Lebensereignisse der jungen Fotografin Anna (Susanne Widl) umfassen eine nur vage definierte Zeitspanne, etwa ein Jahr. Im Laufe dieser Zeit bemerkt sie ihre sich steigernde Niedergeschlagenheit, die sie dazu antreibt, nach immer verdrießlicheren Themen für ihre Fotografie zu suchen. Ihre Erklärung für diesen Zufall ist im mindesten erstaunlich: sie glaubt sich durch die Invasion einer fremdartigen Macht, den Hyksos, angegriffen. Die Hyksos, ein alter, ägyptischer Stamm, sind historisch bekannt für ihr plötzliches Auftauchen und ebenso plötzliches Verschwinden. EXPORT, die von diesem Volk seit ihrer Jugend fasziniert war, gab ihm schließlich einen Ort in ihrem Film.

In diesem klassischen Szenario einer paranoiden Schizophrenie erfährt Anna die Invasion als einen Verdopplungseffekt von Menschen. Ganz ähnlich dem dramatischen Szenario eines Hollywood-Films The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (den EXPORT allerdings zur Drehzeit nicht kannte), in dem die Körper der Menschen äußerlich unverändert bleiben, während sie im Innern von Invasionsmächten besetzt sind, die ihr Verhalten völlig verändern, ist Anna überzeugt davon, dass die feindlichen Hyksos die Erde besetzt haben, da sie in ihrem Umfeld überall zunehmend aggressives Verhalten bemerkt. Ihre täglichen Begegnungen und ihre peinlich genaue fotografische Dokumentation ihrer Eindrücke sind bar jeglicher Weiterentwicklung. Ganz im Gegenteil, beinahe jede Episode von Annas täglichen Erfahrungen enthält die Wiederholung einer Krise oder ein Anschwellen der Angst. Die stattfindende Entwicklung liegt eher auf der Ebene von Annas wachsendem Bewusstsein der Ursache ihres Krankheitszustands als auf der Ebene der Handlung.

Man ist versucht, den Film stilistisch in Begriffen des Realismus zu fassen und als Gegenstück zur abstrakt-symbolischen Eigenart der eingefügten Videos, Fotos oder Installationssstücke anzusehen. Eine derart eindeutige Bewertung ist allerdings bei genauerer Überprüfung nicht haltbar. Es ist offensichtlich, dass der Film mehr realistische Elemente enthält als Einlagen, aber die Grenze zwischen beiden ist durchaus nicht undurchlässig. Das banalste, alltägliche Gespräch, die zufälligsten Gesten können plötzlich mitten im Fluss der Erzählung angehalten und so weit stilisiert werden, dass sie dem Eingefügten ähneln. Der Grund dieser Stilmischung, oder anders gesagt, die Abwesenheit von Eingrenzungen zwischen verschiedenen Repräsentationsebenen, liegt im Prozess der Filmproduktion selbst. Zu Beginn war das Drehbuch eher rudimentär, es beinhaltete eine Abfolge von Szenen, Dialogen und Kommentaren, die dann im Film eingebaut wurden. Für manche Szenen war der Dialog bereits im Drehbuch vorhanden, manchmal entwickelte sich der Dialog spontan, besonders in den Abschnitten, die von Anna und ihrem Liebhaber Peter handeln, und oft wurde der Dialog während der Drehzeit geschrieben. Der Text für Annas Rolle stammt von EXPORT, während Weibel den Text für Peter schrieb, dessen Rolle er auch spielte. Trotz der autobiografischen Aspekte sind diese Passagen jedoch keine realistische Wiedergabe tatsächlich geführter Gespräche; sie betreffen vielmehr konzentrierte Gefühlszustände, wie beide Autoren sie über die Jahre in verschiedenen Beziehungen erlebten. Bei anderen Passagen hingegen wurde das Planen und Schreiben der Kommentare mit größter Sorgfalt unternommen.

(...) Die endgültige Konzeption, Organisation und Komposition von Unsichtbare Gegner fand jedoch am Schneidetisch statt. EXPORT brauchte acht Wochen, um den Film zu schneiden, eine Zeitspanne, in der sie etliche Passagen neu entwarf, gestaltete und ordnete, darunter auch solche, die im Drehbuch bereits vorgeplant waren. Andere Szenen kamen erst während des Schneidens dazu, wie zum Beispiel der Einsturz der Reichsbrücke, der sich damals ereignete. (...) Man kann an der akribischen Aufmerksamkeit, die auf die Collage-Effekte gerichtet ist, die über den gesamten Film zu beobachten sind, das Ausmaß von EXPORTs Liebe zur klassischen Avantgarde, zu Kubismus, Surrealismus und Dadaismus ablesen.

(Roswitha Müller. Aus VALIE EXPORT. Bild-Risse. Aus dem engl. von Reinhilde Wiegmann. Passagen-Verlag, Wien 2002)

Roswitha Müller: VALIE EXPORT. Fragments of the Imagination. (excerpt) engl.

(...) The events in the life of the young woman photographer, Anna (Susanne Widl), loosely cover the period of a year, during which she observes a progressive dejection in her own spirit that drives her to look for increasingly morose subject matter for her camera. Her explanation for this state of decay is surprising, to say the least: she thinks she is affected by what she sees as an invasion of a foreign enemy power, the Hyksos. The Hyksos were an ancient Egyptian tribe renowned for their sudden appearance and equally sudden disappearance. EXPORT, who had been fascinated with this people ever since her youth, finally gave them a place in her film.

In this classic scenario of a case of paranoid schizophrenia, Anna perceives the invasion as a doubling effect in people. Similar to the dramatic scenario of the Hollywood film The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (with which EXPORT was not familiar at the time of shooting), in which peoples bodies remain the same externally but are internally occupied by the invading power that alters their behaviour completely, the increase in aggressive behaviour all around her convinces Anna that the hostile Hyksos have indeed taken over this planet. Her daily encounters and her meticulous photographic record-keeping of her impressions lack development. Instead there is a repetition of crises or a crescendo of anxiety in nearly every episode of Annas quotidian experience. Whatever development does occur is on the level of Annas progressive awareness of what is ailing her, rather than that of plot and action.

It is tempting to conceptualize the script stylistically in terms of realism and in opposition to the abstract-symbolic quality of the inserted video, photo, or installation pieces. Such a clear-cut distinction, however, is hard to uphold upon closer scrutinity. Certainly, there are more realist elements in the scipt than in the inserts, but the boundary is by no means impermeable. The most banal everyday conversations, the most casual gestures can suddenly freeze in the flow of the narrative and become stylized to such a degree that they resemble the inserts. The reason for this mixing of styles, or rather this lack of restraining boundaries between different levels of representation, can be found in the process of film production as a whole. The script was initially fairly rudimentary, not much more than a sequence of scenes and dialogue. Sometimes the dialogue developed spontaneously, especially in the passages that deal with Anna and her lover, Peter. EXPORT supplies the lines for Annas part, whereas Weibel not only wrote but also acted the character of Peter. Although autobiographical, these passages are not realistic reproductions of actual conversations; rather they are a distillation of the states of feelings from a number of relationships experienced by each author over the years. Other dialogue passages, on the other hand, were carefully written and planned.

(...) The final conception, organization, and composition of Invisible Adversaries, however happened at the cutting table. It took EXPORT eight weeks to edit the film, during which time she recomposed many passages, including those provided by the script. The finetuning of matching or contrasting sequences follows principles of association and commentary available to the artist. EXPORTs love of the classical avant-garde, Cubism, Surrealism, and Dadaism can be gauged by the meticulous attention to the collage effect evident in the overall fabric of the film. (...)

(Roswitha Müller. Aus VALIE EXPORT. Fragments of the Imagination. Indiana University Press, 1994, © Roswitha Müller)

VALIE EXPORT: auf der suche nach der heimat legt sich die henkerschlinge um den hals.

auf der suche nach der heimat legt sich die henkerschlinge um den hals.

(VALIE EXPORT. Publiziert Austria Biennale di Venezia 1980, Bundesministerium für Unterricht und Kunst)

VALIE EXPORT, aus Stadtkinoprogramm Nr. 203, Landvermesssung Der österreichische Film 1970 1990

(VALIE EXPORT, aus Stadtkinoprogramm Nr. 203, Landvermesssung Der österreichische Film 1970 1990)

"MOMA's Best Week Ever. Innovator meets Image Maker in dueling retrospectives", by Ed Halter, Village Voice, New York, February 28th, 2007 (Critique)

A multimedia artist before such terminology even existed, Export created her early films, videos, and performances during Vienna's unique streak of politically engaged avant-gardism in the '60s and '70s known as Aktionism: acting out shocking displays of body-horror within a framework of highly structured formalism. Remote...Remote (1973) is one of the most gruelingly extreme of these early works. In it, Export uses an Exacto knifea familiar if latently dangerous artist's toolto slice away at her cuticles and fingertips, displaying the red mutilation with audience-unfriendly close-ups. Eventually, she mixes the blood from her self-inflicted wounds into a dish of milkan evocative nod to both menstruation and motherhood, stripped down to their most primal symbols. Other works attempted to expand the concept of cinema beyond mere theatrical projection: In Touch Cinema (1968), Export walked the streets of Vienna wearing a box with curtained holes in the front, offering passers-by the opportunity to reach inside and feel her chest: Thus the mainstream movies' enduring obsession with women's breasts becomes reduced to its barest essence in a miniature tactile theater for the hands. (In keeping with her confrontational, proto-punk attitude, one performance of Touch Cinema in Germany instigated a riot that left Export with a nasty head wound.)

In later years, Export reworked these themes into a number of feature films; MOMA will be running two. Her longform debut, the enjoyably primitive Invisible Adversaries (1976), melds a Z-grade science-fiction narrative with disorienting chunks of formal experimentation and strident outbursts of manifesto-spieling; in mashing-up Godardian revolution with exploitation-film seediness, Adversaries foreshadows the similarly low-rent obsessions of New York's No Wave underground. The storylinesomething about an alien race called "Hyksos," their name apparently nicked from a historically mysterious people who conquered ancient Egyptquickly submerges beneath Export's disjunctive agglutination of multimedia set pieces, strung together with an almost Monty Pythonesque absurdity. As in her earlier works, Export places women in situations where they become paradoxically abject and strident, even surreally glamorous. In one dreamlike sequence, a woman walks past everyday Viennese shoppers in a pair of ice-skates, metal blades clanking on concrete with every step. In another, she cuts off bits of pubic hair and glues them beneath her nose, creating create a goofy fascist mustache.

More story-driven but no less disjointed, Export's The Practice of Love (1984) is a feminist reworking of film noir in which a female reporter becomes involved with two hommes fatales while investigating a subway murder. More akin to the deconstructions of Yvonne Rainer or Sally Potter, Practice elaborates on the snooping camerawork of classic Hollywood crime flicks by incorporating an array of modern surveillance techniquestelevision cameras, security video, photography, and live-nude-girl peep shows. Though both Adversaries and Practice lose the tightly focused, evocative power of the director's shorter works, they still attest to why a younger generation of women artists has embraced the fearless Export as a spiritual foremother: She's been name-checked by the electro-feminist band Le Tigre and celebrated by the ladyqueer art-collective LTTR (Lesbians to the Rescue). Even in their ambitious imperfections, Export's films serve up more conceptual heft and adult rigor than most anything seen in the featherweight romper-room of today's gallery world; the fangless nudie shenanigans of Julie Atlas Muz, for example, seem like mere college-party clownage in comparison.

Export translated her art into feature filmmaking, but Kiarostami has gone the opposite route. In addition to arriving in person for a comprehensive month-long Kiarostami-paloozawhich includes rarities such as his pre-Revolutionary featurette The Wedding Suit (1976), a Truffautian tale of three teenage boys, and numerous short subjects made for childrenhe'll premiere a multi-channel installation version of his minimal digital-video feature Five (2004), alternatively titled Five Dedicated to Ozu. The theatrical version of the film consists of five unbroken shots of a seashore; even without story or characters, it proves remarkably captivating, like a perfectly crafted object of contemplationor, conversely, a completely transparent window onto nature. In the gallery, it will show as five looping projections, returning the experience to a closer approximation of its environmental source.

--> village voice